Although marriages in ancient Egypt were arranged for communal stability and personal advancement, there is ample evidence that romantic love was as important to the people as it is to those in the present day. Romantic love was a popular theme for poetry, especially in the period of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) when a number of works appear praising the virtues of one’s lover or wife. The Chester Beatty Papyrus I, dating from c. 1200 BCE, is among these. In this piece the speaker talks about his “sister” but this would not have been his actual blood relative. Women were commonly referred to as one’s sister, older women as one’s mother, men of the same age as brothers and older men as fathers. The speaker in the Chester Beatty Papyrus passage not only praises his beloved but presents the Egyptian ideal of feminine beauty at the time:

My sister is unique – no one can rival her, for she is the most beautiful woman alive. Look, she is like Sirius, which marks the beginning of a good year. She radiates perfection and glows with health. The glance of her eye is gorgeous. Her lips speak sweetly, and not one word too many. Long-necked and milky breasted she is, her hair the colour of pure lapis. Gold is nothing compared to her arms and her fingers are like lotus flowers. Her buttocks are full but her waist is narrow. As for her thighs – they only add to her beauty (Lewis, 203).

Women in ancient Egypt were accorded almost equal status with men in keeping with an ancient tale that, after the dawn of creation when Osiris and Isis reigned over the world, Isis made the sexes equal in power. Still, males were considered the dominant sex and predominantly male scribes wrote the literature which influenced how women were viewed.

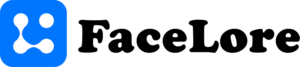

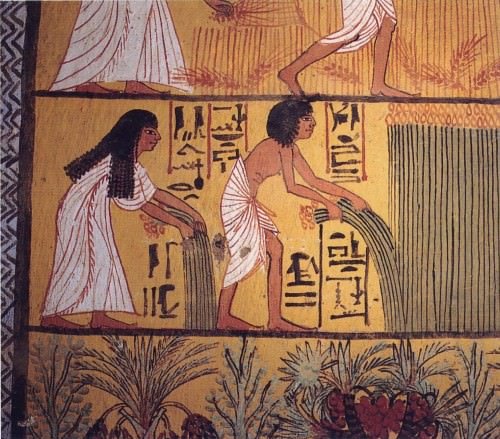

In the above passage, the woman is “milky breasted” (also translated as “white of breast”) not because she was caucasian but because her skin was lighter than someone who had to work in the fields all day. Women were traditionally in charge of the home and upper-class women especially made it a point to stay out of the sun because darker skin signified a member of the lower class peasantry who worked outdoors. These lower class members of society experienced the same feelings of devotion and love as those higher on the social scale and many ancient Egyptians experienced love, sex, and marriage in the same way as a modern individual.

LOVE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

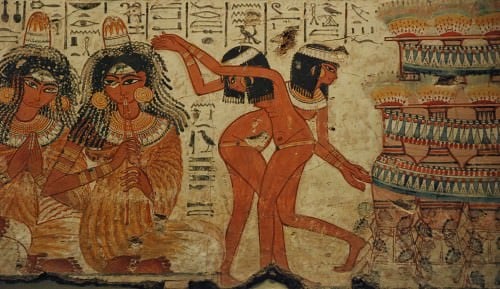

The most famous king of Egypt in the modern day is best known not for any of his accomplishments but for his intact tomb discovered in 1922 CE. The pharaohTutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE), though a young man when he came to the throne, did his best to restore Egyptian stability and religious practices after the reign of his father Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE). He did so in the company of his young wife and half-sister Anksenamun (c. 1350 BCE) and the images of the two of them together are among the most interesting depictions of romantic love in ancient Egypt.

Ankhsenamun is always pictured with her husband but this is not unusual as such images are common. What makes these particular ones so interesting is how the artist emphasizes their devotion to each other by their proximity, hand gestures, and facial expressions. Egyptologist Zahi Hawass notes:

To judge from their portrayal in the art that fills the golden king’s tomb, this was certainly the case [that they loved one another]. We can feel the love between them as we see the queen standing in front of her husband giving him flowers and accompanying him while he was hunting (51).

Tutankhamun died around the age of 18 and Ankhsenamun disappears from the historical record shortly afterwards. Even though the depictions of the two of them would have been idealized, as most Egyptian art was, they still convey a deep level of devotion which one also finds, to varying degrees, in other paintings and inscriptions throughout Egypt’s history. In a coffin inscription from the 21st Dynasty a husband says of his wife, “Woe, you have been taken from me, the one with the beautiful face; there was none like her and I found nothing bad about you.” The husband in this inscription signs himself, “your brother and mate” and in many other similar inscriptions men and women are seen as equal partners and friends in a relationship. Even though the man was the head of the household, and was expected to be obeyed, women were respected as co-workers with their husbands, not subordinate to them. Egyptologist Erika Feucht writes:

In the decorations of her husband’s tomb, the wife is depicted as an equal, participating in her husband’s life on earth as well as in the Hereafter. Not only did she not have to hide her body during any period of Egyptian history, but its charms were even accentuated in wall paintings and reliefs (cited in Nardo, 29).

Sexuality in ancient Egypt was considered just another aspect of life on earth. There were no taboos concerning sex and no stigma attached to any aspect of it except for infidelity, and, among the lower classes, incest. In both of these cases, the stigma was far more serious for a woman than a man because the bloodline was passed through the woman. Historian Jon E. Lewis notes:

Although the Ancient Egyptians had a relaxed attitude to sex between single consenting adults (there was no particular stigma against illegitimate children), when a woman married she was expected to be faithful to her husband. Thus he could be certain that children of their union – his heirs and the inheritors of his property – were his. There was no official sanction against a woman engaging in extra-marital intercourse. The private punishments were divorce, beatings, and sometimes death (204).

While this is true, there are records of government officials intervening in cases and ordering a woman put to death for adultery when the husband brought the case to the attention of authorities. In one case, the woman was tied to a stake outside of her home which she had been judged as defiling and burned to death.

ANCIENT EGYPTIANS & SEX

Stories and warnings about unfaithful women appear frequently in ancient Egyptian literature. One of the most popular is the Tale of Two Brothers (also known as The Fate of an Unfaithful Wife) which tells the story of Anpu and Bata and Anpu’s wife. Anpu, the older brother, lives with his wife and younger brother Bata and, one day, when Bata comes in from the fields for more seed to sow, his brother’s wife tries to seduce him. Bata refuses her, saying he will tell no one what happened, and returns to the fields and his brother. When Anpu comes home later he finds his wife “lying there and it seemed as if she had suffered violence from an evildoer”. She claims that Bata tried to rape her and this turns Anpu against his brother. The story, c. 1200 BCE, is a possible inspiration for the later biblical tale from Genesis 39:7 of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife.

The story of the unfaithful woman was so popular a theme because of the potential trouble infidelity could cause. In the story of Anpu and Bata, their relationship is destroyed and the wife is killed but, before she dies, she continues to cause problems in the lives of the brothers and, later, in the wider community. The Egyptians’ focus on social stability and harmony would have made this subject of especial interest to an audience. One of the most popular stories concerning the gods was that of Osiris and Isis and Osiris’ murder by his brother Set. In the most widely copied version of that story Set decides to murder Osiris after Nephthys (Set’s wife), disguises herself as Isis to seduce Osiris. The chaos which follows the murder of Osiris, in the context of infidelity, would have made a powerful impression on an ancient audience. Osiris is seen as guiltless in the story as he thought he was sleeping with his wife. As in the other tales, the blame is laid on the “other woman” or the “strange woman”, Nephthys.

Besides these tales encouraging fidelity, not a great deal is written about sex in ancient Egypt. There is very little information on sexual positions and practices which is usually intepreted by scholars as meaning the Egyptians placed little importance on the topic. There are no proscriptions against homosexuality at all and it is thought that the long-lived Pepi II (c. 2278-2184 BCE) was homosexual. Unmarried women were free to have sex with whomever they chose and the Ebers Medical Papyrus, written c. 1542 BCE, provides recipes for contraceptives. One such reads:

Prescription to make a woman cease to become pregnant for one, two, or three years. Grind together finely a measure of acacia dates with some honey. Moisten seed-wool with the mixture and insert into the vagina (Lewis, 112).

Abortions were also available and there was no more stigma attached to them than to pre-marital sex. In fact, there is no word for “virgin” in ancient Egyptian; suggesting that one’s degree of sexual experience – or lack of any – was not thought a matter of consequence. Prostitution was not considered a concern either and, as Egyptologist Steven Snape notes, “the evidence for prostitution in ancient Egypt is rather slim, especially before the Late Period” (116). No brothels have been identified in Egypt and prostitution is not mentioned in any written works or legal decisions. The famous Papyrus Turin 55001, which describes various erotic encounters, continues to elude a firm interpretation on whether it is describing sexual liaisons between a prostitute and a client or is a farce. Far more serious than a prostitute or a woman lacking or exceling in sexual prowess was one who could tempt a man away from his wife and family. The Counsel of the Scribe Ani warns:

Beware of the woman who is a stranger, who is not known in her town. Do not stare at her as she passes by and do not have intercourse with her. A woman who is away from her husband is a deep water whose course is unknown (Lewis, 184).

As the Egyptians valued social harmony it makes sense that they would place special emphasis on stories encouraging domestic tranquility. Interestingly, there are no similar stories in which men are to blame. Monogamy was emphasized as a value even among the stories of the gods and male gods usually had only one female wife or consort but the king was allowed to have as many wives as he could support, as could any royal man of means, and this most likely influenced how male infidelity was perceived. Still, the ideal of the ancient Egyptian relationship was a couple who remained faithful to each other and produced children.

MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

There was no marriage ceremony in ancient Egypt. A woman was married to a man as soon as she entered his house with the goods agreed upon. Marriages were usually arranged by one’s parents with an agreed upon bride price and reciprocal gifts from the groom’s family to the bride’s. Pre-nuptial agreements were common and whatever material possessions the bride brought to the marriage remained hers to do with as she pleased. The purpose of marriage was to have children but the couples were expected to love and honor each other. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson comments on this:

Taking a wife appears to have been synonymous with setting up a house. A man was expected to love his wife, as the following exhortation from the sage, Ptah-hotep, makes clear: “Love your wife, feed her, clothe her, and make her happy…but don’t let her gain the upper hand!” Another sage, Ani, proffered a recipe for a happy life: “Don’t boss your wife in her own house when you know she is efficient. Don’t keep saying to her `Where is it? Bring it to me!’ especially when you know it is in the place where it ought to be!” (15).

The groom and the bride’s father would draw up a marriage settlement which would be signed before witnesses and then the couple were considered married. The children of the marriage belonged to the mother and, in the case of divorce, would go with her. Even though warnings of the unfaithful woman were plentiful, women were given enormous freedom in marriage. Historian Don Nardo writes:

In most ancient societies, women were little more than property in the eyes of most men and the emphasis in those societies was almost always on how women could or should make men happy. Granted, like other ancient lands, Egypt was largely male-dominated and for the most part women were expected to do their husbands’ bidding. Still, many Egyptian couples seem to have enjoyed positive, loving relationships (23).

Tomb paintings, and other art and inscriptions, show husbands and wives eating and dancing and working together. In royal families a brother could marry a sister or half-sister but this was discouraged among the rest of the population. For most people, the marriage was arranged for the maximum benefit of both parties and it was hoped that, as they lived together, they would grow to love one another if they did not already. Nardo writes:

Even if he was not deeply in love with his wife, a man could find a measure of happiness in the knowledge that she was content, willingly kept a tidy, well-managed home, and taught the children good manners. He could also take pride in the fact that he worked hard to put food on the table and a roof over both their heads (23-24).

The stable nuclear family unit was considered the basis for a stable society. Although royals were free to marry whomever they chose (following the example of the sister-brother marriage of deities such as Isis and Osiris or Nut and Geb) the common people were encouraged to marry outside of their bloodlines except in the case of cousins. Girls were married as young as age 12 and boys age 15 although the average age seems to have been 14 for girls and 18 or 20 for boys. A boy at this time would have already learned his father’s trade and become practiced in it while a girl, unless she was of royal stock, would have been trained in managing the home and caring for the young, the elderly in the family, and the pets. Historian Charles Freeman notes, “The family was the living unit of Egyptian society. Wall paintings and sculptures show contented couples with their arms around each other and there was an ideal of care of young for old” (Nardo, 25). These marriages did not always work out, however, and in such cases divorce was granted.

EGYPTIAN DIVORCE

The end of a marriage was as simple as the beginning. One or both spouses asked for a divorce, material possessions were divided according to the pre-nuptual agreement, a new agreement was signed, and the marriage was over. Historian Margaret Bunson notes that “such dissolutions of marriage required a certain open-mindedness concerning property rights and the economic survival of the ex-wife” (156). By this she means that even those possessions which the husband may have come to think of as his own were to be divided with his wife according to the original agreement. Anything she had entered the marriage with she was allowed to take with her when it ended. Only a charge of infidelity, amply proven, deprived a woman of her rights in divorce.

During the New Kingdom and Late Period these agreements became more complicated as divorce proceedings seem to have become more codified and a central authority was more involved in the proceedings. Bunson notes how “many documents from the late periods appear to be true marriage contracts. In the case of divorce, the dowry provided by the groom at the time of marriage reverted to the wife for her support or a single payment was given to her” (156). Alimony payments were also an option with the husband sending his ex-wife a monthly stipend until she remarried even if there were no children involved.

ETERNAL MARRIAGE

Marriage was expected to last one’s lifetime, however, and would even continue in the afterlife. Most men only lived into their thirties and women often died as young as sixteen in childbirth and otherwise lived a little longer than men. If one had a good relationship with one’s spouse then the hope of seeing them again would have softened the loss of death somewhat. Tomb paintings and inscriptions depict the couple enjoying each other’s company in the Field of Reeds and doing the same things they did when they were on earth. The Egyptian belief in eternity was an important underpinning to a marriage in that one endeavored to make one’s life on earth, and other’s, as pleasurable as possible so that one could enjoy it forever. There was no otherworldly “heaven” to the Egyptians but a direct continuation of the life one had lived. Bunson writes:

Eternity was an endless period of existence that was not to be feared by any Egyptian. One ancient name for it was nuheh, but it was also called the shenu, which meant round, hence everlasting or unending, and became the form of the royal cartouches (86).

After death, one stood in judgment before Osiris and, if justified, passed on to the Field of Reeds. There one would find all which one had left behind on earth – one’s home, favorite tree, best-loved dog or cat, and those people who had already passed on, including one’s spouse. If one did not treat one’s wife or husband well in life, however, this meeting might never take place and, worse, one could find one’s self-suffering in this life and the next. There are multiple examples of inscriptions and spells to ward off bad luck or circumstances which were thought to be caused by a spouse in the afterlife either haunting a person or exacting revenge from the other side through evil spirits.

Sometimes, the person so afflicted contacted a priest to intercede with the departed and stop the curse. In such cases a man or woman would go to the priest and have a spell written explaining their side of the story and imploring the spirit of the spouse to stop what they were doing. If, on the other hand, the person actually was guilty of some misdeed, they would have to confess it and atone for it in some way. Priests would prescribe whatever atonement was necessary and, once it was accomplished, the curse would be lifted. Ceramic shards of pottery broken at different ceremonial sites give evidence of gratitude to a god or goddess for their intercession in such matters or supplications asking for their help in calling off the spouse’s vendetta.

Another way such conflicts could be resolved was to wipe all memory of the person from existence. This was done by destroying any images one had of them. A famous example of this is the mastaba tomb of the 6th Dynasty official Kaiemankh who had all evidence of his wife Tjeset erased from the walls. One’s spirit only lived on if one was remembered by those on earth and the great monuments and obelisks and temples such as Karnak at Thebes were all efforts at ensuring continued remembrance. Once a person’s name and image were lost their soul was diminished and they might not be able to continue in the Field of Reeds. They certainly would no longer be able to cause any trouble on earth because the spirit would need to be able to see an image of themselves or their name in order to return.

Such problems, it was hoped, could be avoided by living one’s life in mindfulness of eternal harmony and practicing kindness in one’s daily life. Scholar James F. Romano writes, “The Egyptians loved life and hoped to perpetuate its most pleasant aspects in the hereafter” (Nardo, 20). Some of these more pleasant aspects were love, sex, and marriage which one would enjoy eternally as long as one made the most of them while on earth.

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.

A freelance writer and former part-time Professor of Philosophy at Marist College, New York, Joshua J. Mark has lived in Greece and Germany and traveled through Egypt. He has taught history, writing, literature, and philosophy at the college level.COURTESY: ANCIENTEU