A Psychopathological Perspective in Neo-Colonial Era. The thesis shall be published in episodes. A detail of references shall be given in last episode.

Social Psychopathology and Colonialism

The studies on colonialism produced notions and lists of different forms of psychopathology as its outcome. The term colonialism is employed to specify the cultural exploitation and expansionism of Europe over the last 400 year. Ashcroft Griffiths & Tiffin (2000) quoted Said to differentiate colonialism from imperialism, who declares imperialism as a practice, theory and attitude of domination while colonialism is the consequence of imperialism.

The reality and nature of psychopathology and their analysis in former colonies skipped the impact of colonialism on the minds of colonized. Hook (2005) after quoting Steve Biko saying “the most powerful weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed” declares that colonialism in its nature and effect is psychological, as well.

There are two distinct strands to see the relationship between psychopathology and colonialism. First, how colonialism treats psychopathology (or madness), which is the minuscule aspect of current discourse, and second, the etiological role of colonialism in the formation of psychopathological trends among the colonized.

Ernst’s (1991) gives a detailed account of the development of psychiatric set ups in India and its coinciding with the British imperial advancement. Though the Asylums were founded with the approval of East India Company but it was a private business until they were taken over by the English establishment after reining tightly over the state machinery. These madhouses, as Ernst calls them, were built only for confining people with mental health issues. The development of large asylums,  initially, in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay was mainly meant to serve the European patients but at later stages Indian patients were also admitted in to them. The colonial racist trends were obvious in the architecture, therapy and the running of these asylums. For example, the asylum in Bombay was divided into two sections, one half was dedicated to twenty one European patients while the second half was there for seventy two Indians. The patients were divided into two categories, first class and second class. The patients in the first class were those diagnosed with temporary weakness, nervousness, fatigued or affected intellect would belong to the officers class and stay in India for brief treatment or convalescence. But, (European) patients belonging to the working class would be labelled as perfect Idiots and maniacs. Since, their insanity was considered as a threat to the myth of White superiority over the natives; this working class would face forced repatriation back to the Britain.

initially, in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay was mainly meant to serve the European patients but at later stages Indian patients were also admitted in to them. The colonial racist trends were obvious in the architecture, therapy and the running of these asylums. For example, the asylum in Bombay was divided into two sections, one half was dedicated to twenty one European patients while the second half was there for seventy two Indians. The patients were divided into two categories, first class and second class. The patients in the first class were those diagnosed with temporary weakness, nervousness, fatigued or affected intellect would belong to the officers class and stay in India for brief treatment or convalescence. But, (European) patients belonging to the working class would be labelled as perfect Idiots and maniacs. Since, their insanity was considered as a threat to the myth of White superiority over the natives; this working class would face forced repatriation back to the Britain.

The asylums in Africa were different in their basic approach from Indian ones. “From Algiers to Lagos, from Mombasa to Cape Town, psychiatrists, colonial administrators and settlers focused their concerns about madness on indigenous rather than European populations. Officials fretted about how to define insanity in an alien culture, and psychiatrist from both British and French schools published widely on indigenous psychopathology and the political and social implications of the African mind. These doctors (like their colleagues in India) also cared for European patients but their preoccupation was the identification and classification of madness in Africans” (Keller 2001, p.305). This focus was, probably the main reason why a lot of attention has been paid to find out the traces of connections between the medical knowledge and colonial conquests. The first response was from Mannoni (1990) who considered colonialism not only pathological but pathogenic as well. In his views it is impossible to understand the complexities of colonial power merely by looking at structural and economic aspects of it. Colonialism is not only for profit but it craves for some other psychological satisfaction, which made it more dangerous. Nandy (1983) confirms this notion with examples. According to Mannoni, the abuses (with all their psychological impacts on the abused) of colonial system can not to be justified solely in terms of economic interest and exploitation (Chassler 2007).

McCulloch (1995) agreed with Ernst’s (1991) account about the role of these asylums as being the institutions of social control as they mainly served the political purposes. For example he concluded that ethnopsychiatrists, colonial governments and societies of settlers, they all attributed the political protests by the indigenous population with the pathological impulsivity.

The more important aspect of psychopathology in colonial and postcolonial studies is the etiological one. From Mannoni to Fanon to Bhabha and Ashish Nandy, and off course many others, made phenomenal contributions on the subject.

Frantz Fanon (1952), although, criticized Mannoni in his Black Skin, White Masks, but acknowledged his honesty and thanked him for sincerity (p. 61). Philip Chassler (2007) gave some background information about Mannoni’s work Psychology of Colonialism. This book was written in the aftermath of rebellion (a “holy war against colonialism” according to Macey; quoted by Lane, 2002) in Malagasy against the French Colonizers in 1947. Some estimates suggest 80,000 but some other would give the figure of 100,00 people killed by the French. In his introduction, Mannoni raises a very basic question, which is raised almost by every scholar on colonialism. Chassler quotes Mannoni, “I became preoccupied  with my search for an understanding of my own self, as being an essential preliminary for all research in the sphere of colonial affairs” (p.72). One can see how Mannoni was referring to the notion, later adopted by Fanon, about violence as an outcome of the failure in sticking with own racial identities. Lane (2002) quoted the comments on the outcome of Mannoni’s own analysis of himself as “an imaginary, perhaps ghostly reader, devoid of character, race and nationality- a Malagasy, in other words, and a French citizen, or neither” (p. 132). This is exactly, what proved to be the starting point of postcolonial psychopathology, the relation between an individual and his reality. The psychosocial distortion; a root cause and a stepping stone for psychopathology, becomes tangible when psychic and external realities are fused in each other. This distortion, Mannoni feels at two different levels of his existence; dependent and inferior. He, using Adlerian analysis called it a failure in adaptation, the same account of “inferiority complex” he was criticized by Fanon, when he said about an adult Malagasy that the “germ of (inferiority) complex was latent in him from childhood” (Fanon, 1952. p. 62). The context set by Mannoni has been proved to be difficult to overturn by others. Colonialism, in its essence, cannot be “grasped outside the consideration of affective economies of desire, fear and identification” (Hook 2012, p. 103)

with my search for an understanding of my own self, as being an essential preliminary for all research in the sphere of colonial affairs” (p.72). One can see how Mannoni was referring to the notion, later adopted by Fanon, about violence as an outcome of the failure in sticking with own racial identities. Lane (2002) quoted the comments on the outcome of Mannoni’s own analysis of himself as “an imaginary, perhaps ghostly reader, devoid of character, race and nationality- a Malagasy, in other words, and a French citizen, or neither” (p. 132). This is exactly, what proved to be the starting point of postcolonial psychopathology, the relation between an individual and his reality. The psychosocial distortion; a root cause and a stepping stone for psychopathology, becomes tangible when psychic and external realities are fused in each other. This distortion, Mannoni feels at two different levels of his existence; dependent and inferior. He, using Adlerian analysis called it a failure in adaptation, the same account of “inferiority complex” he was criticized by Fanon, when he said about an adult Malagasy that the “germ of (inferiority) complex was latent in him from childhood” (Fanon, 1952. p. 62). The context set by Mannoni has been proved to be difficult to overturn by others. Colonialism, in its essence, cannot be “grasped outside the consideration of affective economies of desire, fear and identification” (Hook 2012, p. 103)

Fanon (1963/2001) took the notion of psychosocial distortion more directly and could see it from both colonized and colonizer’s perspective. He shows how psychopathology gets into a vicious cycle, where it develops a preset apparatus of perpetual origination of its own.

The look that the native turns on the settler’s town is a look of lust, a look of envy; it expresses his dreams of possession all manners of possession: to sit at settlers table, to sleep in settler’s bed with his wife if possible. The colonized man is an envious man. And this the settler knows very well; when their glances meet he ascertains bitterly, always on the defensive. ‘They want to take our place’. It is true, for there is no native who does not dream at least once a day of setting himself up in the settlers place (p. 30).

At the same time every settler, not infrequently fears the violent reprisals of the native. Fanon goes back to the question, which Mannoni posed to himself as well, of identity. “Because it is a systematic negation of the other person and a furious determination to deny the other person all attributes of humanity, colonialism forces the people it dominates to ask themselves the question constantly: in reality, who am I?” (Fanon 1963/ 2001, p. 200) This constitution of destabilization of subjectivity promotes and strengthens the state of fantasy, but unlike Freudian fantasy it does not deal with the question of what I want or what I fear rather it incites and initiates a process of questioning from a place of profound scepticism.

In his attempt to explain the psychopathology Fanon (1963) gives case histories of patients he examined and tried treating them during his job as a psychiatrist. He outlined the main reason of psychopathology as oppression. “In the period of colonization when it is not contested by armed resistance, when the sum total of harmful nervous stimuli overstep a certain threshold, the defensive attitudes of the native give way and they then find themselves crowding the mental hospitals. There is thus during this calm period of successful colonization a regular and important mental pathology which is the direct product of oppression” (p. 201).

Fanon used a Psychiatric term frequently to describe the condition of his patients; a reactive psychosis, which today is called Brief Psychotic Disorder, BPD (APA, 2000). DSM-IV-TR gave the lists of symptoms like delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech and grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior. The symptoms may emerge after going through a condition which is stressful to almost anyone in similar circumstances in person’s culture. Sometime the onset is quick but sometime it is delayed. Fanon was very careful in selecting the label as it is still relevant after 50 years. It was the “bloodthirsty and pitiless atmosphere” which gave rise to the reactive psychoses. Colonialism caused psychosis but only a reactive one which is basically a reaction against violence of colonial encounter. The violence, observed and suffered collectively by a society has epistemic, cultural, psychic and physical aspects to cause unprecedented and unique historical trauma. To live through the trauma, psychosis becomes a route to escape or if we borrow from Laing, it becomes a strategy to live in this unliveable world. Since it is a strategy, Fanon asks a question; what does the black man want. He insists on black man to remain black in his interaction with the white. But when the black does not stay black, Fanon calls this as epidermalization of inferiority and this is what he is worried about in “Balck Skin: White Masks”. In result of adopting this strategy black man’s ego is collapsed, self-esteem is evaporated and he is ceased to be a self-motivating person. (Sardar 2008). It is difficult, even to assume Fanon’s being unaware of Wilhelm Reich’s book, Mass Psychology of Fascism. It’s first German edition (Die Massenpsychologie Des Faschismus) was published in 1933. Reich (1995) described this little man who craves for authority but with the attitude of rebelliousness. This mishmash attitude created many brutal and fascist dictators. We all know about these reactionary dictators who obliterated their own people instead of those they were angry with. Fanon wants to enable the man of colour to understand, the psychological elements that can alienate his fellow Negro (Fanon, 2008). Fanon describes the Negro “caught in the (psychoanalytic) tension of demand and desire” as a split; a psychotic split. Negro’s fantasy of occupying the master’s place (and palace) without leaving slave’s dungeon of avenging anger is a psychotic split. The anger against the colonizer is inhibiting and impeding not liberating.

Homi. K. Bhabha is different from Mannoni and Fanon, as he was born in 1949 in Mumbai, two years after the finish of colonial rule over India. In his own words, “my early life was caught on the crossroads that marked the end of Empire: the postcolonial drive towards the new horizon of a Third World of free nation” (Bhabha, 1994. p. X). What is postcolonial obviously was a question for Bhabha to start with. Can one tell us the starting point of postcolonial? Bhabha treats the question differently; “Our existence today is marked by a tenebrous sense of survival, living on the borderlines of the present, for which there seems to be no proper name other than the current and controversial shiftiness of the prefix ‘post’: postmodernism, postcolonialism, postfeminism. The ‘beyond’ is neither a new horizon, nor a leaving behind of the past” (Bhabha, 1994. P.2). Looking at his writings and his analysis one can safely define postcolonialism as a “discourse of colonialism”.

It is an apparatus that turns on the recognition and disavowal of racial/cultural/historical differences. Its predominant strategic function is the creation of a space for a ‘subject people’ through the production of knowledges in terms of which surveillance is exercised and a complex form of pleasure/unpleasure is incited. It seeks authorization for its strategies by the production of knowledges of colonizer and colonized which are stereotypical but antithetically evaluated. The objective of colonial discourse is to construe the colonized as a population of degenerate types on the basis of racial origin, in order to justify conquest and to establish systems of administration and instruction (Bhabha 1994. p. 70)

The complex doublings continue to find their relevance in the colonial literature. In the world (particularly after 9/11) the complexities of neo-colonial wars, globalization, and cultural confrontation are reduced to “clash of civilization”. This discourse of colonization converts the political into cultural. The title of the third chapter of his book is The other question: Stereotype, discrimination and the discourse of colonialism, is very edifying. The important notions of the discourse of colonialism are; the stereotype, mimicry, hybridity, the uncanny, the nation and cultural rights.

The Stereotype provides validation and rationality to the colonizer’s act of colonizing. The leading explanation is the supposed inferiority. Colonized are frequently, though implicitly labelled as lazy, stupid and uncivilized. However, Bhabha very successfully identifies strange but fundamental anxiety underneath every stereotype. The knowledge attained from ‘stereotype’ is used to establish full control. As far as “The Other Question” is concerned it suggests the inseparable twos where one is always undermined. One obvious effort is to assume and maintain the stereotype as ‘fixed’, this is impossible without invoking psychopathology (Huddart, 2006).

Mimicry in Bhabha’s writing denotes to the effort of the colonized to adopt and adapt colonizer’s culture. Neither this mimicry is of slavish kind nor are the colonized allowed to be assimilated into colonizer’s culture. For Bhabha, “it is an exaggerated copying of language, culture, manners, and ideas” (Hudart, 2006, p.57). Mimicry reflects the essential struggle of the colonizers to make colonized to be like them but not identical. The mimicry is indicative of ambivalence of colonial structures. The question is whether the ambivalence is accidental or integral part of colonialism. Bhabha (1994) suggests that this ambivalence or mimicry is never complete, rather it unveils colonialism’s grand narrative of humanism, and enlightenment.

The Hybridity is one of the most disputed notions presented by Bhabha. The term itself refers to the cross pollination of two species to create the third one. Bhabha refers to the interdependence of colonized and colonizer for the construction of their subjective identities.

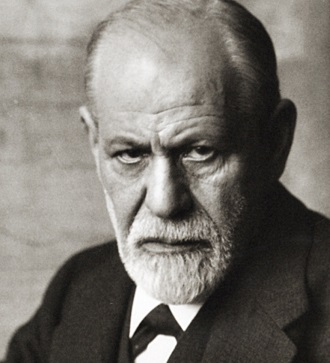

The Uncanny, is a slippery concept which Bhabha borrowed from Freud. As it is described above, the colonizer creates monstrous stereotypes due to his own anxiety around the identity. The colonized resist the colonial rule through mimicry, strategy of doubling or repetition. According to the Freudian definition “the uncanny is that species of the frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been familiar” (Freud, 2003. p. 124). In psychoanalysis, uncanny is not something one can directly access or control as these feelings are primarily involuntary. The concept of uncanny is very close to what Freud calls as repetition compulsion, where mind repeats involuntarily the traumatic experience to resolve them. Uncanny, at one hand brings the individual back to what is familiar (childhood or home) but it carries its direct opposite (the unknown, the unhomely) as well. This to and fro movement is another example of ambivalence. The Uncanny indicates the focus of psychic energy of colonized to determine his future (unknown) direction while entangled with past (the familiar). Basically, by using this term, Bhabha wants to reflect the dual characteristics of the identities of colonized and colonizers and time wise fitful strategies of the colonized.

The Nation is important in the discourse of anti-colonialism and postcolonialism. In the anti-colonial struggle the colonized found solace in the national identities. Bhabha rejects the well defined and stable identities of nationalism because it puts all emphasis on pedagogy instead of performance. That’s why he wants to keep this aspect of identity as open as possible.

Through Cultural Rights Bhabha points out how through hybridity and in the discussion of human rights minority cultures are ignored in their postcolonial lives.

Through these notions of discourse Bhabha assimilated psychoanalysis to describe the state of postcolonial society, mind and personality. These are interaction mechanisms evolved in interaction between colonized and colonizers. This is a parallel to Freudian defense mechanisms. Unlike the  Freudian notion it is not a one way process, as colonized and colonizers are both involved in it. The pathology lies in lacking the insight, frequency and fixation around the practice of these interaction mechanisms. One can adopt different mechanisms at different times or different mechanisms to deal with different conflicts. In a particular society, different groups may evolve different interaction mechanisms. Being unaware of using these mechanisms and sticking, fixating and insisting on one mechanism and ignoring others altogether, may be a pathological manifestation in itself. One can object on the overwhelming use of psychoanalysis, but social psychopathology has yet to find a better theoretical orientation for its formulation. The presence rather dominance of psychoanalysis in postcolonial discourse, in itself, is evidence of psychopathological trends in the interaction of colonized and colonizer. However, like Mannoni and Fanon, Bhabha is convinced that colonialism is pathological and pathogenic at the same time. This discussion confirms that all efforts to assess and estimate the current psycho-social and psycho-political trends of former colonies, must understand the pathological trends caused by the colonialism and its perpetuating forms.

Freudian notion it is not a one way process, as colonized and colonizers are both involved in it. The pathology lies in lacking the insight, frequency and fixation around the practice of these interaction mechanisms. One can adopt different mechanisms at different times or different mechanisms to deal with different conflicts. In a particular society, different groups may evolve different interaction mechanisms. Being unaware of using these mechanisms and sticking, fixating and insisting on one mechanism and ignoring others altogether, may be a pathological manifestation in itself. One can object on the overwhelming use of psychoanalysis, but social psychopathology has yet to find a better theoretical orientation for its formulation. The presence rather dominance of psychoanalysis in postcolonial discourse, in itself, is evidence of psychopathological trends in the interaction of colonized and colonizer. However, like Mannoni and Fanon, Bhabha is convinced that colonialism is pathological and pathogenic at the same time. This discussion confirms that all efforts to assess and estimate the current psycho-social and psycho-political trends of former colonies, must understand the pathological trends caused by the colonialism and its perpetuating forms.

Note: The Article has been published before and has not been updated.

Dr. Akhter Ali Syed is a famous Psychologist and writer. He is currently working in Ireland as Principal Psychologist. He also has a keen interest in Philosophy, religions, History and Humanity.