In 1570, Elizabeth I was in a bind. She had been excommunicated by the Pope, and her country was shunned by the rest of Europe. To avoid ruin, England needed allies. The queen sought help from a surprising source: the Islamic world.

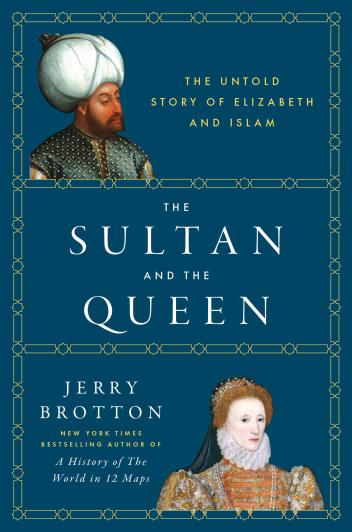

The Tudor period has supplied endless popular entertainments—from Cate Blanchett’s Elizabeth movies to the television series The Tudors—but this story has rarely been told. Jerry Brotton explores the forgotten history of English-Muslim alliances in his new book The Sultan and the Queen. Speaking from his home in Oxford, England, Brotton explains why Elizabeth believed Islam and Protestantism had more in common with each other than with Catholicism and how this cultural exchange may have inspired Shakespeare’s plays and turned the queen’s teeth black.

From Donald Trump to Brexit supporters, many Westerners view Muslims as a threat and want to close the borders. But 500 years ago, Queen Elizabeth I made alliances with the Shah of Iran and the Ottoman Sultan. What can Elizabeth I’s relations with the Islamic world teach us?

A lot. They can teach us that there’s a form of pragmatic exchange and toleration and accommodation, which trumps ideology. One of the key stories in the book is the issue of trade and the way trade collides with religions. The reason Queen Elizabeth develops this relationship with the Islamic world is theology initially. She’s establishing a Protestant state and England has become a pariah in Catholic Europe. So she reaches out for alliances with the Islamic world.

What flows from that is an exchange of trade and goods, regardless of sectarian and theological differences. Elizabeth is not reaching out to Sultan Murad III because she’s a nice person and wants religious accord. She is doing it for hard-nosed political and commercial reasons.

Elizabeth’s alliance with Murad III was essential to her self-preservation, yet this story has largely been left out of Tudor history. Why do you think that is?

In the last few years, there’s been a parochial identification of the Tudors, reflected in the way they have featured in recent TV shows, like The Tudors. It has become an index of Englishness, connected to whiteness and Christianity. But it never tells the wider story of what’s going on internationally. I started working on 16th-century maps and what the maps were telling me was that there was an exchange between the Islamic and Christian worlds, which wasn’t being told in the official histories.

Look at Tudor portraits. It’s all Orient pearls, silk from Iran, or cotton from the Ottoman territories. The English language changes, too. Words suddenly enter, like sugar, candy, crimson, turban, and tulip, which have Arabic or Persian roots. They all come in with the trade with the Islamic world.

Elizabeth did her best to convince Sultan Murad that Protestantism and Islam were two sides of the same coin and that the true heresy was Catholicism. I’m confused …

What she does very shrewdly, when she starts to write to the Sultan in 1579, is say: Look, you and I have many similarities in terms of our theology. We do not believe in idolatry or that you should have intercession, i.e., a saint or a priest will get you closer to God. Protestantism says you should read the Bible and then you will be in direct contact with God. Sunni Islam says the same: You have the Koran, the word of the Prophet, you do not need saints or icons.

Elizabeth is doing this politically. What she’s saying is, you’re fighting Spanish Catholicism; I’m fighting Spanish Catholicism. What nobody mentions, of course, is Christ. [Laughs] Islam believes Jesus is a prophet, but not the son of God. So in all the correspondence, they step around this issue. They always talk about the fact that they both believe in Jesus but not how they believe in Jesus.

The first recorded Muslim woman to enter Britain was called Aura Soltana. She has an amazing story, doesn’t she?

She does. Another extraordinary figure, Anthony Jenkins, one of the earliest Englishmen to establish diplomatic and commercial connections with Persia, is on his way back to England, traveling up the Volga River, in what we now call Greater Russia. In Astrakhan, he buys this woman, Aura Soltana. It’s not clear whether this is a slave name or the name of the place she’s come from, but he takes her back to England.

At around this time, a similar figure is established as a lady-in-waiting in Elizabeth’s court. If it’s the same person—and I believe it is—she becomes a kind of fashion adviser to the queen, telling Elizabeth how to wear certain kinds of shoes or materials. Her exotic background made her exactly the kind of person to whom Elizabeth could say, “Oh, you’ve just come back from Moscow, what are the latest catwalk fashions?”

There’s a tantalizing painting of an anonymous woman by Marcus Gheeraerts, called The Persian Lady,which some people speculate is of this woman. She’s dressed in a very opulent, oriental fashion. It could be our lady Aura Soltana, a slave who ends up in Elizabeth’s bedroom, dressing her. It’s an amazing story.

Among other goods, English merchants imported over 250 tons of Moroccan sugar into London every year. Is it true Elizabeth’s love of sugar turned her teeth black?

Yes! [Laughs] We have accounts by European travelers, who describe Elizabeth as a small woman with blackened teeth from eating so many sweet meats and candies. The predominant importation of sugar at that time was from what we would now call Morocco, as a result of Elizabeth’s Anglo-Islamic alliance with the Saadian Dynasties. It’s quite ironic. The Moroccans are fighting the Spanish while Moroccan sugar is destroying Elizabeth’s teeth, and English armaments are helping the Moroccans kill other Christians. [Laughs] Elizabeth liked anything sweet. Candied fruit was a big thing. Everything is just steeped in sugar!

Today, ISIS forcibly converts non-believers. Elizabethan merchant Samson Rowlie experienced a similar fate, didn’t he?

He did. The issue of conversion with somebody like him is fascinating. He’s a merchant from Great Yarmouth, in Norfolk, who travels on an English commercial venture in 1577 to the eastern Mediterranean. Turkish pirates capture him. He is castrated, turned into a eunuch, and taken to Algiers. He converts, takes the name Hasan Agar, and becomes the chief eunuch and treasurer of the head of the Ottoman controlled city of Algiers! The English write to him about ten years later, about issues of trade. They say, “We believe you are probably still a Protestant. Would you like to come back?” Rowlie replies, “No way! I have a palace in Algeria. It’s nice weather here. Why would I want to go back to Great Yarmouth?” [Laughs]

You have many similar stories of people converting to Islam or, in the language of the time, “turning Turk.” It’s relevant to the current situation in the Middle East because, invariably, it’s Christians and Protestants who are embracing Islam, not the other way around. There are accounts of people who willingly embrace Islam because, in contrast to the way in which we see that culture today, the Muslim world is seen as tolerant and embracing difference.

You write that, “London’s playhouses were in the grip of a fascination for staging scenes and characters from Islamic history.” How was this reflected in Shakespeare’s plays?

Shakespeare is fascinated by Moors, particularly. He’s also using the language of Turks and Persians throughout his plays. One of the earliest plays he writes, which we usually date around 1592, is Titus Andronicus. The main agent of evil, the baddie, in that play is called Aaron. He is described as a blackamore, which means he’s from northwest Africa, from the Barbary States. He causes all the chaos: bloody rape, pillage, mutilation, absolutely awful! People say, “Oh, that’s the predominant view of the Muslim in this period.”

Four or five years later, Shakespeare writes The Merchant of Venice. Another Moor pops up there called the Prince of Morocco. He’s a rather benign, elegant figure who’s a suitor to Portia, the heroine of the play. So Shakespeare is playing with different versions of these Muslim, Moorish characters. You get the evil Aaron and the rather noble Prince of Morocco.

Around 1601 Shakespeare then writes Othello, which draws on both versions. He is the irrational, violent, racist figure of the black man. He’s also this very elegant, powerful military commander: The Moor of Venice. Shakespeare is not moralizing. He’s drawing on this history of Anglo-Islamic relations to say, who is this man? Do we trust him? He might save us but he might also kill us all in our beds.

Post 9/11, it is one of the most frequently performed tragedies because of the complexity of its relationship with religion and ethnicity, which we are now seeing in North Africa and the Middle East. It’s become about much more than simply a black man destroyed by a white man.

You grew up in one of England’s most multicultural cities, Bradford, in Yorkshire. Talk about your early life—and how it inspired your interest in this subject.

For me it is profoundly personal because I am not from an elite background. My father was a deep-sea fisherman; my mum was a barmaid. I went to a state school just outside Bradford, where I was born. There was a multiculturalism we embraced, which was my version of Englishness. I played cricket with Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims; we were in the same religious studies classes. Post 9/11 and 7/7, when London was attacked, it was a real shock for me. What had gone wrong? Growing up at that point, those issues of sectarian differences were never in play.

What was the biggest surprise for you in researching this story, Jerry?

Following characters traveling through a world that is now in meltdown. They’re moving through places currently under control of the so-called Islamic state. What they’re doing at that point is encountering an Islamic world that is powerful, sophisticated, and superior to the culture that produced them: Protestant English culture. There’s an attempt to understand and accommodate, and to get on with each other.

That was the real shock and surprise for me, in a good way. There are Elizabethan Englishmen talking about the distinction between Sunni and Shia in the 1560s, when many people today don’t understand the distinction. So, hopefully the book is one little attempt to offer another kind of story of toleration and accommodation.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.

courtesy: NationalGeographic