FROM THE STONEWALL RIOTS IN NEW YORK back in 1969 to the recent legalization of same-sex marriages, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) issues have been central in discussions about civil rights and harassment in the Western world. This dialogue has forced individuals, organizations and governments to question their values and beliefs. Many religious organizations have turned to their scriptures, their followers and their spiritual traditions for guidance on how they should respond.

Well-known spiritual leaders from various faiths have stepped forward to present the views of their respective belief system, but there has been relative silence from the “movers-and-shakers” of the Hindu faith. Now, however—with recent deliberations regarding anti-sodomy laws by the Indian Supreme Court, and growing populations of Hindus in European and North American countries, where these debates have been making headlines—these religious heads are speaking up. Their opinions on LGBT individuals run the gamut from outright condemnation through muted disapproval, apathetic indifference, conservative tolerance, to genuine acceptance. Recent surveys indicate that 3-7 percent of every nation’s population is gay, making a global population between 225 and 525 million.

LGBT History in India

Politically and socially conservative factions in India claim that homosexuality or alternative gender identities are an influence of Western ideas. This idea is based on the false assumption that being a homosexual or alternative-gender individual is a lifestyle choice. In fact, gender identity is an inborn trait. Evidence suggests that prior to British legislation targeting what they regarded as “unnatural sexuality,” homosexual and transgender people coexisted with heterosexuals in pluralistic Hindu communities. Ruth Vanita, a scholar who has written extensively on South Asian LGBT themes, wrote in her book, Love’s Rite: Same-Sex Marriage in India and the West, “Under colonial rule, what was a minor strain of homophobia in Indian traditions became the dominant ideology.”

Prior to the 19th century, historical sources that specifically refer to LGBT lives and lifestyles are relatively scarce. However, we can see a subtle intermingling of such perspectives and characters in Hindu legends and stories. Ancient Tamil Sangam literature compiled between the 3rd century bce to 4th century ce contains stories about transgender individuals, referred to as pedi, and stories of deep love and attachment between men, such as the King Koperunchozhan and Pisuranthaiyar, and the King Pari and poet Kabilar.

The Kama Sutra, a classical text on human sexual mores and behavior, also acknowledges same-sex attraction and activity. The text describes individuals of the “third sex,” tritiya prakriti, and lesbian women, svairini.(For a comprehensive look into LGBT references in Indian literature, see Same-Sex Love in India edited by Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai.) Outside of literature and religious stories, one can also look at the 11 century Khajuraho temples in Madhya Pradesh—famous for their erotic sculptures—to see same-sex love represented amongst the various temple carvings.

Under the dominion of the British Raj, homosexuality was codified and made illegal under the British penal code. In 1861 India saw the creation of the infamous Section 377, which criminalizes “carnal intercourse against ‘the order of nature,’” encompassing “sodomy, buggery and bestiality.”

Over 150 years later, Section 377 lives on and has become a hot-button issue for LGBT activism. The movement to repeal the law was begun in 1991 by AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (the AIDS Anti-Discrimination Movement) and was continued in the 2000s by the Naz Foundation (India) trust. In 2009, in a historic move, the Delhi High Court struck down the law in a manner as to legalize consensual homosexual relations between adults. The case was challenged, however, and in 2013 the Supreme Court set aside the 2009 judgment, thus criminalizing homosexual activity once again. The main argument of the justices was that this was a law to be debated and repealed by parliament, not by the courts. Violation of Section 377 can be punishable by a fine and imprisonment of up to ten years.

Section 377 and its Effect Today

The Deccan Herald of January, 2015, reported that nearly 600 arrests were made under Section 377 in 2014 alone. In one case, a tech worker in Bangalore was turned in by his wife. Not surprisingly the threat of being jailed for sexual activity casts a shadow of fear and persecution over the LGBT community in India. Activists are well aware of cases where the fear of entrapment has been used to blackmail, harass and bully LGBT people.

A 2014 World Bank report, “The Economic Cost of Homophobia,” lists a few preliminary statistics on the harassment faced by LGBT individuals in India. Gay men were up to 12 times more likely to suffer depression, and the HIV prevalence was 15 times the general population, most likely due to lack of healthcare access and education. LGBT individuals were up to 14 times more likely to suffer suicidal thoughts. These results, however, are preliminary, based on limited methodology, and show the need for more extensive academic research in the years to come.

Priya Gangwani, the editor of Gaysi Magazine in India, says, “Thanks to 377, we see the brutal symptoms of exploitation, hierarchizing identities, prejudice and discrimination.” Nevertheless, she goes on to affirm that the fight against 377 has fueled and united the LGBT communities and their allies. “Many stepped out of the closet in response to the Supreme Court’s judgment. It has made people protest, resist, rebel, choose, love and be anyway they want without bothering with what the law allows or does not,” Priya observes.

Even in the shadow of 377, we hear glimmers of good news for LGBT individuals, as demonstrated through city pride parades, the occasional same-sex marriage and the increasing visibility of gay and transgender leaders. India and Nepal, both Hindu majority countries, have been among the first and the few to legally recognize the “third sex” or transgender individuals, thus enabling them to benefit from basic citizenship rights and welfare policies. In August 2015, Nepal issued its first “third-gender” passport to a citizen, and in September 2015 the government made history by explicitly enshrining equal rights and freedom from discrimination for LGBT individuals in the constitution. This puts Nepal ahead of several Western liberal democracies, which still may not provide full constitutional protection from discrimination.

So what are activists looking to as next steps? Pallav Patankar, director of programming at Humsafar Trust, India’s pioneering AIDS welfare NGO, is energized about the work that lies ahead. “Our efforts are twofold. The first is sensitizing the masses through pride marches, through appearances and interviews on television and in the news, and getting our presence out there. The second level is to talk to our politicians to make them understand that we are part of their voter base, and that popular morality may not always be right.”

Patankar stresses that, due to the laws in India, the work done by Humsafar and other LGBT and AIDS-related organizations is limited to those above the age of 18, thus leaving adolescents at great risk. He agrees with Priya Gangwani that the Section 377 ruling actually gave a new wind to the gay rights movement in India. “Had the ruling given us our rights, that still would not have made it a mass public opinion. This could be a great opportunity.”

LGBT Themes in Stories and Theology

When Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami spoke at the 2014 Permian Basin Interfaith Panel about Homosexuality and Hinduism, he said: “Hinduism doesn’t have a structure where it can come up with one view. It doesn’t have a singular authority that says this is our way of looking at homosexuality. It has many independent groups, some liberal and some conservative.”

Today’s various Hindu theologies emerged from a landscape of peaceful debate throughout history. Different schools of thought have always argued over topics ranging from the nature of the divine to the avoidance of certain foods, without accusing opposing views of being heretical or blasphemous. Ancient Hindu society had room for opposing viewpoints and lifestyles, and it was in this atmosphere that many LGBT groups flourished.

While many modern Hindus see LGBT individuals as a product of foreign—specifically Western—influence, ancient Hindu scriptures detail LGBT individuals, their characteristics and the roles they played in ancient society. Throughout Vedic-era literature, society is divided into three main groups: pums-prakriti, heterosexual males; stri-prakriti, heterosexual females; and tritiya-prakriti, those of the “third nature.”

Tritiya-prakriti encompasses a variety of minority sexual orientations and gender identities. This identity is broken down into further specific subgroups, including napumsaka (gay men), sandha (transgenders), kliba(asexuals), svairini (lesbians), and kami/kamini (bisexuals). Portrayals of these groups and individuals in the literature were usually expressed in a descriptive and dispassionate voice. Their presence in ancient Hindu society was widely known, accepted and regarded as a natural aspect of humanity.

Devdutt Pattanaik is the respected author of 30 books and over 600 articles on Hindu mythology. When asked whether Hinduism regards these individuals in a positive or negative light, he responded, “The idea of judgment, control or commandment is alien to Hindu thought. So LGBT being seen as positive or negative springs from our desire to judge, which is not Hindu.”

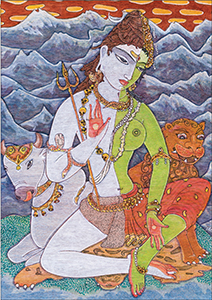

Judgment against LGBT individuals does not have a strong foundation within Hindu literature, while gender fluidity and same-sex relations are commonplace. Hindu Deities often appear in multiple gender forms, and many stories detail their same-sex and opposite-sex romantic interactions and episodes. Gianna Love, an activist and independent cultural researcher, details the importance of these episodes in the formulation of Hindu values. “The effect these narratives can have on cultural value formation and conceptions of sex and gender is of utmost value. Deities with gender and sexual fluidity, and their stories, form very real belief systems, cultural values and traditions with real followers that are themselves of various non-binary and non-heterosexual identities.”

This is exemplified in the worship of Sri Iravan in southern India, a hero from the Mahabharata. Folklore states that Iravan offered to sacrifice himself in order to ensure the success of his army, but desired to marry and experience conjugal bliss before his death. As no parent was willing to offer their daughter, Krishna himself took the form of Mohini, married Iravan and fulfilled his worldly yearning. Today Iravan is a popular patron saint for individuals of the third gender. In an annual festival at a temple near Koovagam, India, thousands of transgender men reenact the legend by ceremonially marrying Iravan and then mourning his death the following morning.

The enchantress Mohini, an incarnation of Krishna/Vishnu, is found throughout various episodes in Hindu literature. She often tricks demons into self-destruction through seduction and allurement. In one story she deceives the demon Bhasmasura into turning against himself his ability to reduce anyone to ashes. In another episode she offers to distribute the divine ambrosia of immortality to the angelic devas and demonic asuras, but serves only the devas. Mohini also, through union with the God Siva, becomes the mother of Lord Ayyappan, a hugely popular Deity in South India.

Gender fluidity of Hindu deities resulted in not only the switching between male and female as binaries, but through shades of gray between the two poles. The imagery of Ardhanarishvara, an androgynous Deity that is half Lord Siva and half Goddess Shakti, is widespread, and sculptures often depict the Deity bearing both female and male attributes. A similar story involves Prince Sudyumna, who inadvertently entered into a forest in which all men were cursed to become women. Lord Siva subsequently modified the curse so that Sudyumna would spend alternating months as a male and a female, and eventually Sudyumna married the God Budha (Mercury) and spent his female months as Budha’s wife and his male months as his student.

In the Mahabharata, the warrior Arjuna assumes the form of a male-to-female transgender, disguising himself as a dancer named Brihannala to obtain shelter with King Virata. Brihannala’s speech and character so impressed the King that he instructed his daughter, Uttara, “Brihannala seems to be a highborn person. She does not seem to be an ordinary dancer. Treat her with the respect due to a queen. Take her to your apartments.”

While many of these examples can be seen as progressive towards LGBT issues, other sources are clearly proscriptive. Hindu scriptures are divided into two categories: shruti, divinely revealed scriptures—the Vedas and Agamas—which deal with human spirituality and the nature of the ultimate Divine Being; and smriti, secondary scriptures, which often deal with law, orthodoxy and societal duties. While shruti literature is almost universally recognized and revered, the authority of smriti literature is often debated between various Hindu groups. Many of the proscriptions against homosexuality arise from the smriti, a lesser category of sacred literature.

Of these, the Manusmriti is one of the texts cited most frequently in debates by those who oppose the recognition and acceptance of LGBT individuals. The Manusmriti deals amply with one’s sacred duties, known as dharma. One of the central themes of dharma in Manusmriti is the need to produce offspring for the continuation of society. At one point, it states that “men who do not copulate for the sake of progeny are unworthy of making offerings to the gods and ancestors.” According to those who rely on the Manusmriti, individuals who do not participate in gender roles that promote classical nuclear families, and sexual relationships that do not result in progeny, can be considered as failing the aims and missions of Hindu life.

However, as Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami stated, there is no single Hindu view on any issue, including recognition of LGBT individuals. Some liberal viewpoints counter the purported need to form heterosexual relationships and produce progeny by citing the strict prohibitions against men of the third gender marrying women, as detailed in the Naradasmriti. Also, these liberal interpretations view same-sex attractions and their pursuit as falling under kama, or “sensual pleasure”—which, after all, is one of the four aims of Hindu life. The Kama Sutra even romantically describes the intimacy and commitment of LGBT couples with the words: “There are also third-sexed citizens, sometimes greatly attached to each other and with complete faith in one another, who get married together.”

While Hinduism’s folklore does not clearly establish the practical place of LGBT individuals in society, leaving the matter open for discussion, one needs to consider the Hindu tradition of acceptance and inclusivity. The culture of free debate and open conversation without the threat of persecution is what allowed different schools of thought to flourish, and for “third-natured” individuals to live unmolested. It is when this freedom breaks down that travesties occur and the beauty and breadth of Hinduism is forsaken.

A Rajasthani story tells of two women, Teeja and Beeja, who are married under the pretense that Beeja was a man so her father could acquire Teeja’s dowry. On their wedding night, however, the women accept each other as life partners, infuriating the rest of the villagers. Attempting to gain acceptance among the villagers, the female lovers undergo trials and tribulations; at one point they even use magic to temporarily change Beeja’s gender. Ultimately, however, each retains her natural gender and they flee to the forests, sheltered by the spirits who dwell there. In one version of the tale, the spirits ask the women whether they are afraid to be in the presence of apparitions. The women reply, “No, we are not. We fear humans more.”

Same-Sex Marriage in a Hindu Context

One of the cornerstones of Hindu practice is the focus on family life. Hinduism prescribes the four progressive stages of a dharmic life as the four ashramas. They are brahmacharya (student), grihastha (householder), vanaprastha (retire) and sannyasa (renunciate).

Can a committed same-sex relationship be considered the grihastha or family stage? Can the Hindu marriage ceremony have room for couples who do not conform to gender norms and expectations?

Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami spoke on this issue at the Midland Interfaith Conference in 2014: “Marriage is helpful to create stable relationships. So, therefore, we take the Hindu point of view, shared by many, that gay marriage stabilizes relationships and is a good thing.”

We interviewed four different couples who are either already married or are planning their wedding ceremonies in the near future, to hear what Hindu marriage means to them.

Monica Elise Davis and Colleen Ryan

Monica and Colleen met in law school. Before their romance began, they bonded as study buddies preparing for the California bar exam. Several months later, they knew they were more than friends. They were engaged in December of 2011, and kept an eye on the developments towards marriage equality in California. They could not have timed their wedding better. Merely six weeks after marriage equality became legal in the state, Monica and Colleen tied the knot with a Hindu ceremony in Napa Valley.

Monica, who was raised Hindu, and Colleen, who was raised Catholic, thought deeply and carefully about the weight and meaning of their wedding. They were inclined towards a Hindu ceremony, especially since they could find nothing in Hindu scripture that opposed their union, unlike in the Catholic tradition.

The ceremony wound up being an intermingling of rituals from both faiths that they held dear, with Colleen’s uncle officiating. The brides exchanged garlands and walked around the sacred fire seven times. Who led whom around the fire? “We thought about that,” says Monica, laughing. “We took turns in who led, and in the last round we tried to walk side by side, which was really hard to do. We were trying to be true partners in our ceremony.”

The ceremony included more all-American details, such as the personal vows, the exchanging of rings and the kiss at the end. Monica who is chairperson of Trikone, a Bay Area LGBT organization, confides “We were in front of all of our friends and family, and growing up in the US everyone else kisses at the end! We wanted to show that this relationship is real; we’re married!”

Sunil Sharma and Maarten Cornelis

Sunil and Maarten’s wedding—a grand three-day affair—took place at the estate of Kasteel Van Leewergem in Ghent, Belgium, in August 2015. By conducting an authentic Hindu ceremony in the heart of Belgium, Sunil and Maarten guaranteed an intermingling of their families and cultural backgrounds.

Cultural unification is important to Sunil and Maarten, who practice Hinduism and Buddhism respectively. They met in Los Angeles in 2010 and got engaged in 2012 while on vacation in Belgium. Maarten had all of his family members dress up in traditional Indian clothing and tell Sunil “Welcome to the family,” each in a different language. Finally, Maarten proposed to Sunil in Sunil’s mother tongue, Kannada.

The couple weren’t sure they could have a traditional Hindu wedding until they serendipitously met a Hindu priest in Europe earlier this year. Before agreeing to conduct the wedding, he put the pair through a rigorous conversation to truly examine their intentions. Sunil shares, “It felt like a pre-wedding interview, like in a Catholic wedding.” Sunil and Maarten passed their priest’s test with flying colors, which further solidified their commitment to their wedding and to one another.

Their wedding guests experienced a mostly traditional Hindu ceremony—including a spectacular entrance for both grooms in their own baraats (entrance procession)—with the rituals of the Ganesh puja, blessings from the parents and older siblings, fire sacrifice and the saptapadi, or seven steps.

“Instead of concerning ourselves on the gendered parts of the ceremony, we wanted to focus on being connected as two people in love,” says Sunil.

Maarten agrees. “Marriage, any marriage, is two souls meeting and committing to each other in front of God.” He pauses, and adds, laughing, “In front of Gods. Sorry.”

Now that they are married, Sunil and Maarten plan to start a family, through adoption. “We’re traditional,” says Maarten, “being married first, then having kids and starting a family.” Sunil chimes in, “I’m looking forward to spending the rest of my life with this guy.”

D’Lo and Anjali Alimchandani

For D’Lo and Anjali Alimchandani, their wedding ceremony is more than just a personal commitment and a reaffirmation of their Hindu beliefs and upbringing. It’s a political symbol.

D’Lo is a transgender Sri Lankan-American performance artist and political activist. You may have caught him on HBO’s “Looking,” Amazon’s “Transparent” or the Netflix series “Sense8.” D’Lo’s work consistently marries his art and activism; and for Anjali, that was one of the things that drew her to him from the beginning.

“I had seen a couple of his shows and had a big crush on him,” says Anjali. They started dating in 2010, and in 2013, began talking about the possibility of having a more formal, traditional commitment. They were both careful and considered in their choice—they identify as queer progressives, and even the concept of a state-sanctioned marriage held little appeal for them.

Their ceremony resembled a traditional Sri Lankan Tamil wedding, although they incorporated some rituals from the Sikh-Punjabi tradition as well. Anjali says, “Just the visibility of the two of us queer people taking part in this ‘traditional’ ceremony, usually reserved for straight people, is such a powerful statement for our communities to see.”

D’Lo sees this ceremony as an important milestone in his relationship with his parents. “Throughout my queer life, it was about distancing myself from them,” he says. But this ceremony was an important opportunity to get them actively involved, and to seek their blessings for the union.

In Anjali’s words, this ceremony is less about turning away from their communities and more about turning into them. They are excited about the enthusiastic response to their invitations. D’Lo recounts, “I wrote to my Appa’s family and explained what was happening. Almost all of them wrote back—people I didn’t even know—saying, ‘We’re coming!’”

Mala Nagarajan and Vega Subramaniam

When Mala and Vega got married at the Seattle Aquarium in 2002, they were making history simply by holding one of the first visible Hindu lesbian marriages in North America. They went on to become an even more iconic couple for the South Asian LGBT community when they joined the lawsuit against the state of Washington to overturn the Defense of Marriage Act in 2004. Although their case was rejected on appeal by the state Supreme Court in 2006, the lawsuit energized and accelerated the continued fight for gay rights. Now, in 2015, both the state of Washington and the state of Maryland, where Mala and Vega currently live, recognize their union as legal.

Thirteen years into their marriage, the couple reflect back on their South Indian Hindu ceremony and what it meant to them. “I didn’t just want to have another party when we got married,” says Mala. “I wanted to reclaim my religion.”

Vega agrees. Despite being an atheist, she says that planning the Hindu wedding felt natural to her. “These traditions belong to us as much as they belong to a straight couple.”

They carefully designed the ritualistic aspects of the wedding. “We were really intentional,” says Mala. “We were not going to do a ritual that replicated male and female divisions. We wanted something that talked about us as equals. And I felt like that was possible within the frame of Hinduism.”

What still makes them laugh, however, is that when it came down to the day of the wedding, the priest and their family members wound up inserting and modifying rituals on the spot. “We thought—well, we’ve arrived!” says Vega. The interference of family members actually felt like a tacit blessing. Mala and Vega felt embraced and accepted.

The couple believe that the recognition of same-sex relationships marks a generational shift. “All of the more established religions are losing millennials,” says Vega. Even though Mala’s parents are among the founders of the Sri Siva Vishnu Temple in Maryland, they have not felt fully welcome there. “It’s very clear to me that the temples have to change with the times to stay relevant.”

Personal Stories

The relationship between Hinduism and LGBT issues is a strained one. Tejal Kuray, an environmental consultant and social activist, learned about this at a young age growing up in New Jersey. When she asked her mother about homosexuality, her mother responded that homosexuals were dangerous and most certainly not welcome in her household. “My mother, at best, sometimes insisted that she didn’t have a problem with gays, per se,” Tejal reminisced, “but why did they have to press for something like rights?

Tejal made an active effort to shape her family’s views and help them come to terms with LGBT issues. She offers advice to other Hindu Americans who try and reshape the views of more intolerant individuals in their families. “I wish that more open-minded Hindus would talk about LGBT rights with their parents the way my sister and I did with ours. All the rallies and protests in the world would not have changed my mother’s opinion—but her children championing gay rights in the living room certainly did.”

This grass-roots activism has helped welcome many LGBT Hindus out from hiding, but while some have been accepted with open arms, others have stayed in the shadows due to hurtful words spoken around them. Radhika (a pseudonym) had known she was a bisexual from a young age, having felt drawn to the idea of another woman’s love. “I have always known I liked girls and guys,” she insisted. “But I also knew the toll it would take on my family. So I had to decide to not let myself get too close to any girl, not let myself completely fall in love, because in the end I would have to be with a man if I wanted to keep my family in my life.”

Radhika knew her family’s views on same-sex attractions. When she was younger, her father reacted with anger and disgust when he came across an Indian gay character on a television show. “Words like ‘disgusting’ and ‘immoral’ were thrown around between my older brother and father for the next few minutes.” She tried explaining that attraction went beyond choice, and that many examples of same-sex attraction had been noted throughout the animal kingdom. Her protests were disregarded. “We’re human,” her family responded. “We know better.”

Radhika initially was angered by her family’s attitude towards LGBT issues, viewing it as blatant bigotry. However, as time passed, she began to empathize with their views and understand where they were rooted. She explains that society is often trapped between tradition and concepts that seem foreign or new. “Religion is simply a collection of ideas that help people deal with uncertainties in the world; and it often does just that. Letting go of any aspect may make people unravel and lose faith in their survival.”

Mala and Vega today, still happily married

Although she stays on the sidelines and keeps her identity a secret from her family, Radhika hopes for a future where she can fully embrace both her Hindu and bisexual identities. She imagines a day where she can enter a temple with someone she loves and not face people’s judgment or contempt. She believes additional exposure is the solution that will eventually bring about that change. The more exposure people have to the LGBT community, the more they can see that we are all human.

Her hope, though, is tentative. She feels that the damage done by her family’s views is in many ways permanent, and that the emotional scars will be always present. “I will never be as close to my family as I will be with my friends. I hide so much from them; and although it hurts, I know it’s for the better.”

On Allies, Coming out and Family Life

As societies evolve, families find themselves grappling with issues and ideas that had not presented themselves to recent generations past. Hindu families, with hundreds of years of tradition and expectations to contend with, can find themselves at a unique and sometimes painful crossroads when a child, sibling, spouse or even a parent acknowledges an alternative sexual or gender identity.

As a young kid growing up in Connecticut in the 90s in a devout and traditional Hindu family, Raja Gopal Bhattar was faced with several conflicting messages about sex, sexuality and gender identity. Raja remembers going to a library, setting up a separate email account, and emailing HINDUISM TODAY, desperate to get a real answer from a trusted spiritual source. Soon an email was sent back. “It was the sweetest email,” Raja remembers. “I don’t even remember who it was at this point, but they were an editor at HINDUISM TODAY, and they said, ‘God made you the way you are. As long as you love yourself and you’re a good person; you’re fine.’”

Raja is now the director of the LGBT Campus Resource Center at UCLA, where he is a PhD candidate in Higher Education. Raja identifies as gender-queer and prefers the pronouns “they,” “them” or “their” when being referred to, rather than “him” or “her.” Raja traces back their journey towards growth and acceptance to that first supportive moment of validation from Hawaii, and the knowledge that they could still be a part of the Hindu tradition they were raised in.

Raja speaks to the unique issues of Hindu LGBT individuals and their families. “Our desi families, coming from our unique immigrant experience, have instilled this guilt and responsibility in us, since they have sacrificed so much to come to this country. So, there’s a lot of pressure on young adults to achieve the ‘right’ career and ‘right’ marriage.”

Dr. Pemmaraju Rao, a physician and psychiatrist based in Texas, elaborates on the “double-whammy” of expectations for LGBT youth: Even straight individuals have to struggle with specific cultural notions of who their partner should be.

Taking this into perspective, what should a young, queer Hindu individual do when considering the path of coming out of the closet? By and large, experts advocate caution and safety above everything else. “There’s this white American notion that if you’re not out to everyone, you’re not queer enough,” says Bhattar. “You don’t have to come out to your family ‘till you feel safe—your safety is most important. Part of our authenticity is living in that complexity.”

Pallav Patankar, from the Humsafar Trust in India, encourages LGBT youth to be strong and sure in themselves and to have a solid emotional—and financial—safety net before coming out to their family. He points out that the coming-out process will continue through one’s entire life—to one’s immediate family, to the workplace, to the neighborhood, to every new person one meets.

Dr. Rao encourages the parents of gay, lesbian and trans children to let go of their fears and traditional paradigms, and to truly listen to the feelings of their children instead of trying to control who they are. He urges parents to accept: “If this is their dharmic path, then nothing can stop that, despite our fear.”

The process of integration and acceptance is very much a two-way path. Children have to be as accepting and patient with their parents as their parents must be with them. “Understand that the current generation comes from a very different framework than the previous generation,” says Bhattar. “I can’t expect them to change to accept myself, just as it is the other way around. It’s a process, and it’s a process both ways.”

One source of hope for LGBT individuals can be Hinduism itself. “Look to Hinduism,” says Dr. Rao. “See how it embraces both the masculine and the feminine. Your karma and your past lives have led you to this point. It is a proactive choice by your soul. Your uniqueness gives you an extraordinary power to offer to the world, as a gift.”

Conclusion

Over the course of our investigation into this topic, what has become clear is the diversity of voices and opinions within the global Hindu community. During the 2004 Kumbha Mela at Ujjain, HINDUISM TODAY conducted interviews with religious leaders at the gathering. Some of the swamis who came from a more international and cosmopolitan background voiced the liberal view of Hinduism being compatible with homosexuality, while others espoused the position that the Hindu tradition does not permit same-sex relationships.

In short, the situation remains complicated; but the need of the hour is continued conversation and introspection. India and Hinduism find themselves at a crossroads today. With increasing global awareness of LGBT rights, with same-sex marriage grabbing the headlines and the fight against Section 377 gaining steam, it is crucial for Hindu communities around the world to recognize and address this issue that affects countless individuals and families worldwide.

MADHURI SHEKAR, 29, was raised in Chennai and now resides in Los Angeles. She is an award-winning playwright whose plays include: A Nice Indian Boy (about gay marriage in a Hindu family) and In Love and Warcraft.

Courtesy: Hinduism Today

HARI H. VENKATACHALAM, 29, is an American Hindu activist and currently resides in Tampa, Florida, where he is pursuing a Masters in Public Health at the University of South Florida.