Hamraz says one Pakistani industry has never failed: the rumour industry. It goes into full production when a political change is in the offing

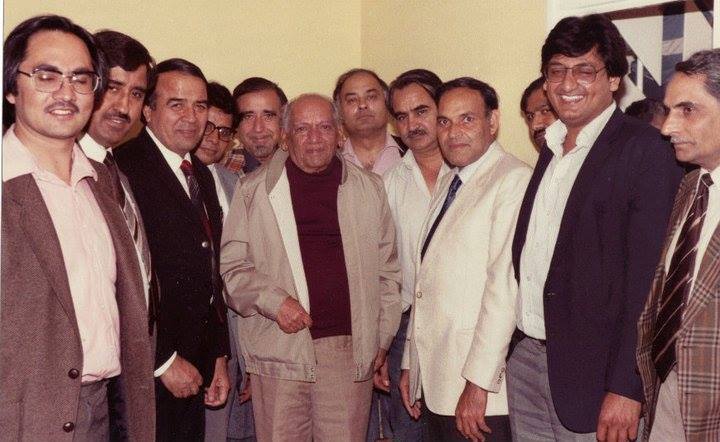

Hamraz Ahsan, who has now lived in London for many years, was one of the young and committed journalists in the Lahore of the late 1960s and the following decade who formed the vanguard of the progressive and leftist politics of the time. He and a bunch of fiery young men worked with labour unions, farmers groups and teachers and journalists to fight the onslaught from the reactionary, right-wing movement funded and backed in large part by the establishment, which wanted to block the spread of a brand and style of politics that led, first to the formation of the Pakistan Peoples Party, and later to its ascent to power. It has been said that a revolution eats its own children first, a fact of history which also came to pass in Pakistan . Many of these idealistic, brave young men who had no interest in material advancement, found themselves on the wrong side of what they thought was the peoples government. Hamraz Ahsan lost one newspaper job after another and was in and out of jail several times, but his faith in his credo and the dream of a progressive, free and secular Pakistan never wavered.

He struggled on in Pakistan right into the dark days of Zia ul Haq, when he finally decided that the military regimes torture cells were not going to be his future. His escape from Pakistan merits a separate story and, if written out, could even make a movie. Some years ago, Hamraz began to write an account of his life, of his growing up in the city of Gujrat and moving to Lahore , getting drawn to the left movement and eventually into journalism. That book remains incomplete, but he has now published a collection of his short pieces written from London during his exile years. That old patron of many lost causes, Agha Amir Hussain of Classic, Lahore , has published it under the title Harf-e-Saada . Much of the book is made up of pieces written about London , but Pakistan remains the backdrop, which is what gives the book its special flavour. One piece is based on his meeting with Margaret, the English woman from Newcastle , wife of many years to Chacha Chaudhry Zaman Ali, Tamgah e Khidmat, from Mirpur, who jumped ship before Pakistan s birth and settled in England .

Chacha Zaman Ali truly was the patriarch of immigrants from our part of the world in England . He helped thousands of them find work and settle down. He never quite learned to speak English and had his own version of it. He came to earn the respect of more than one generation of his new and old countrymen. To the Pakistanis and the Azad Kashmiris, he was Chacha Zaman Ali, though some called him Baba Zamanaan.

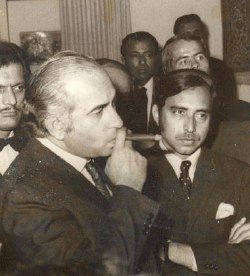

In 1979, after Zulfikar Ali Bhuttos execution, a huge protest rally was held in Hyde Park, London , where Chacha Zaman Ali brought several busloads from Birmingham . I can see him standing on the roof of a parked vehicle addressing the crowd that included Murtaza and Shahnawaz Bhutto, Ghulam Mustafa Khar and Tariq Ali (it was the first time Tariq Ali had joined a purely Pakistani protest march, and I am happy to say that I had some hand in it). Hamraz recalls a Quran khwani in the central Birmingham mosque where Chacha Zaman Ali, despite his years, was himself serving food to those who had come from far and wide to pay homage to the executed leader. When President Ayub Khan visited Britain , he authorised Chacha Zaman Ali to recommend those to whom Pakistani passports would be issued. Many illegal but law-abiding and hard working Pakistanis were thus legitimised. The least Pakistanis and Kashmiris living in Britain can do is to build a memorial to that fascinating, truly public-spirited stalwart who could not pronounce his wife Margarets name (she remained Magray to him all his life).

Having been an inmate of several of Pakistan s jails under different governments, Hamraz writes, Our jails were designed by the British as was the jail manual, which is the funniest legal document in the world. A prisoner can keep cigarettes but no matches, a comb but no mirror. While no cell can contain an even number of prisoners, odd ones are permitted. Two, four and six disallowed; three, five and seven allowed. Why? No one knows. The welfare provisions in this manual have never been implemented. These provisions quantify even the pieces of meat that a prisoner should get twice a week, plus the exact weight of the bread he is to be served and how much ghee must go into his serving of lentils. Hamraz also writes that there is one industry that has never failed in Pakistan : the rumour industry. It goes into full production when a political change is in the offing. Since General Pervez Musharrafs advent, the burden on this industrys production units has become rather heavy, and it has had to go into a 24-hour cycle.

Hamraz remembers a visit to Lohar Galli in Azad Kashmir, which offers a breathtaking view of the Jehlum and Kishen Ganga rivers coming together. This was Zulfikar Ali Bhuttos favourite place whenever he came visiting. Hamraz found the two rivers flowing lazily into one another reminding him of an insincere embrace between two Pakistanis. Were the rivers like this when Bhutto sahib used to visit? he asked his escort. There was so much water in these rivers then. Today, there is dust everywhere. Hamraz writes, I wondered where the water that used to flow in these rivers and fall from our eyes has gone. Did it die out in the rivers or in our eyes? Who took this water away from us? Who will be held to account for this?

Benazir Bhutto once said, Hamraz notes, that she believes in miracles, otherwise who could have predicted that Zia would suddenly cease to be or she would become prime minister twice? And although the lines that follow were written by Hamraz some years ago, their validity today is in the realm of the uncanny.

Our people are always waiting for miracles because our entire country has been run on that basis. These days many are going from one place to another in search of some miracle. There are those who are desperately trying to perpetuate the miracle of their having come to power in the first place. Some are waiting for a stray miracle to fall into their laps. Others are running off to America because they know that fate has assigned miracle-making responsibilities to that country, at least in the current century. We will just have to wait and see on whose head the bird of good fortune lands. Will he choose a new head or return to a head on which he once had his perch? It is also possible that the bird may become lazy and decide to remain on the same head where it has been nesting for the past several years. In that case, those seeking miracles will have to brace themselves for temporary disappointment.

In one piece, Hamraz Ahsan wonders why the walls and newspapers of Pakistan are plastered with advertising promising antidotes against black magic but carry no advertising as to the acquisition and practice of black magic. Yes, why not indeed?

Courtesy: Friday Times

Khalid Hasan was a famous Pakistani writer, Philosopher and activist. Khalid worked on many posts and is known for his beautiful prose and translations. Khalid died in 2009 in USA.