Shakespeare has famously written “The fault dear Brutus is not in our stars but in ourselves”. This pithy statement could be appropriated to Pakistani current political situation by reversing the order. “The fault dear People is not in ourselves but in our stars.” The political development of representative institutions is contained not by individuals but the system itself as it functions in Pakistan. Digging a little into post-colonial historical evolution of state in Pakistan informs that this current fixation of political narrative on accountability is not new rather have resurfaced time and again.

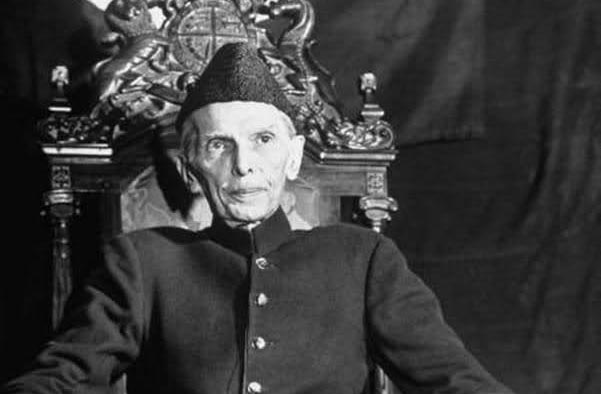

Since the very beginning the relationship between state, government and society, in Pakistan, is structured in a very unique way. The overdeveloped non-representative institutions were in-charge of governance without any recourse to democratic accountability. The initial decisions, taken by the founding father himself, kept the viceregal tradition of colonial governance model intact. Cabinet and legislative assembly was by-passed in running government through constituting a post of Secretary General. While the Governor General in India was just ceremonious head, in case of Pakistan the effective power in the name of Governor General was actually grabbed by the bureaucracy. Jinnah, who was terminally sick at the eve of independence, effectively used by this bureaucracy to silence Bengali dissent, subdue Baloch self-determination and sending off Frontier provincial assembly. This precedent was later used to straighten the local politicians in all provinces. Rawalpindi conspiracy case asserted, with other things, the vital importance of Army on political stage. And in order to placate it a permanent position in cabinet was offered to Ayub Khan, who in few years become the first military ruler of Pakistan. So, since from very beginning the effective and real power cobbled by and remained in the hands of civil-military oligarchy. However, in order to legitimize their rule this oligarchy always needed a facade of representative regime. So, a post-colonial system of power emerged where “Political field” allowed to thrive but in a regulated environment. Out of these muddy waters emerged a culture of governance in which top concern of every political actor remained “access” to this state oligarchy.

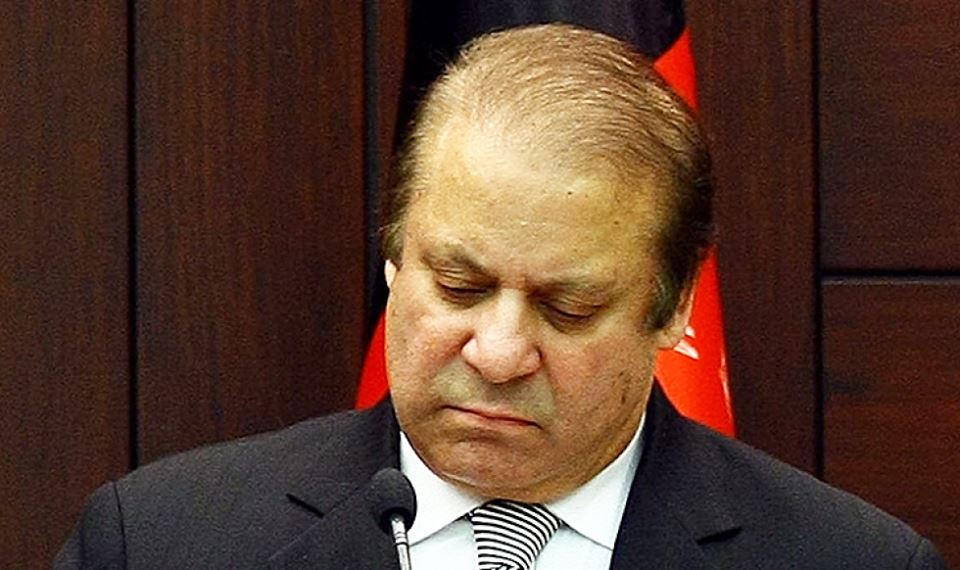

This post-colonial model of governance retained the colonial continuity of picking and choosing social groups and classes for regulating social and political life. State oligarchy built alliances with dominating social groups i.e. landlords propped up by previous (colonial regime). Increasingly, new social classes were welcomed into the ruling club. However, the entry was remained strictly regulated by the state oligarchy. Great amount of recorded evidence is available reminding the relative dependence of landlords, capitalists, and “salariat” classes on state oligarchy for their political power and social mobility. Whenever, any politician crossed the invisible red line of “national interest” (the interest of oligarchy) she was cut to size directly or indirectly. The role of judiciary , third arm of state, in this story was to ,without exception, legitimize all non-constitutional actions of state oligarchy. The so-called revolt by Ifthikhar Chaudry was not a revolt of judiciary as an institution but was an individual act of bravado that provided a chance to all anti-Musharraf factions (within oligarchy too) to combine their political capital against the increasingly unpopular General. Later decisions on “NRO” and barrages of “Suo mottos” were mostly against civilian executives in the name of accountability. In current crisis again the guns of accountability are again directed at politicians.

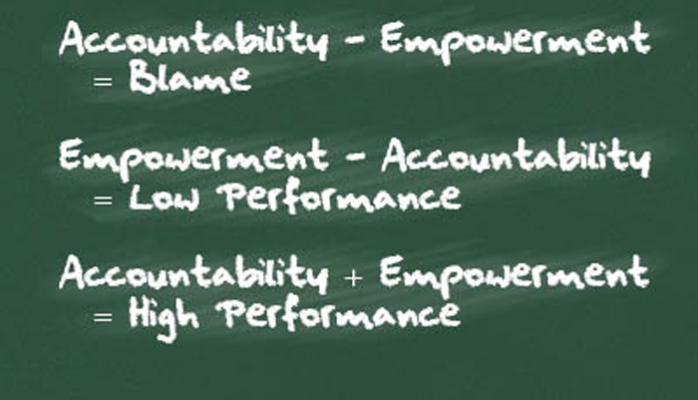

In this context I have serious reservations about any narrative of accountability in Pakistan. In paper accountability for any model of governance is a prerequisite. However, in Pakistan, accountability (and its twin sister corruption) is a slogan always raised before a regime change. First Legislative assembly in 1953 was sent home in the name of corruption. Zia and Musharraf both grabbed power in order to make civilian governments accountable and two prime ministers during recent “PPP regime” learnt lessons of accountability in superior courts of law. This selective practice of accountability performs following functions for the political and state system at large; (a) keep the non-representative arms of state in control (b) damage the stature of any errant politician and party (c) legitimize the capture of state power by non-representative institutions in public eye d) block formation of any emancipating political mobilization of dominated classes.

Hamza Alavi, the doyen of Pakistani Sociology, has succinctly explained these bureaucratic games to retain the state-power in the hands of state oligarchy. But there is little or no discussion that how such  interventions in the name of accountability block any process of politicization which could leads to the collective action of lower classes in Pakistan. In order to understand this duplicitous and layered phenomenon recourse to a forgotten theoretician of oligarchy General Sher Ali is essential. He advised Yahya khan that to keep the state power of military intact it is important to develop a non-coercive method of legitimization of such hold on power. To put simply, there is a need to develop a system in which state oligarchy can enjoy privileges of power means to keep power without any fear of legal or popular responsibility. This logic in practice means that everyday governance is better to leave in the hands of civilians while the real decisions of Meta governance can be kept within the reach of oligarchy. On the plains of foreign, economic and interior policy all shots must be (or at least with the consent of) called by the oligarchy. While building roads and providing Gas and sanitation facilities could be left to the civilians. Any civilian government has to make happy both sides of coin, the people and the deep state. It has to distribute patronage and share in the economic pie both above and below. To placate the state oligarchy it gives a blind eye to the capital accumulation of state institutions and their control on foreign and domestic policy. While in order to meet the genuine demands of people networks of informal political associations are formed to dispense state resources and services. These informal networks of intermediaries, goondas, and brokers are formed and sustained by using the development fund. Which means less and less public services availability to citizens and more and more expenditure of public resources to maintain loyal political networks. Increasing population and stagnant economic growth means government can’t co-opt all the social groups and political networks. Selective practices of dispensing patronage lead to unpopularity of any government within days. To regain popularity, natural course of action for any government, in such situation, is to assert authority on meta levels of public policy for accumulating more resources to keep a favorable public opinion. Which lands it into a conflict with the deep state and amidst new slogans of accountability. This repeated cycle is going on and on since last 70 years without any critical rapture. Thus those ,the politically and economically excluded, have the right to believe and profess that “the fault is in our stars”.

interventions in the name of accountability block any process of politicization which could leads to the collective action of lower classes in Pakistan. In order to understand this duplicitous and layered phenomenon recourse to a forgotten theoretician of oligarchy General Sher Ali is essential. He advised Yahya khan that to keep the state power of military intact it is important to develop a non-coercive method of legitimization of such hold on power. To put simply, there is a need to develop a system in which state oligarchy can enjoy privileges of power means to keep power without any fear of legal or popular responsibility. This logic in practice means that everyday governance is better to leave in the hands of civilians while the real decisions of Meta governance can be kept within the reach of oligarchy. On the plains of foreign, economic and interior policy all shots must be (or at least with the consent of) called by the oligarchy. While building roads and providing Gas and sanitation facilities could be left to the civilians. Any civilian government has to make happy both sides of coin, the people and the deep state. It has to distribute patronage and share in the economic pie both above and below. To placate the state oligarchy it gives a blind eye to the capital accumulation of state institutions and their control on foreign and domestic policy. While in order to meet the genuine demands of people networks of informal political associations are formed to dispense state resources and services. These informal networks of intermediaries, goondas, and brokers are formed and sustained by using the development fund. Which means less and less public services availability to citizens and more and more expenditure of public resources to maintain loyal political networks. Increasing population and stagnant economic growth means government can’t co-opt all the social groups and political networks. Selective practices of dispensing patronage lead to unpopularity of any government within days. To regain popularity, natural course of action for any government, in such situation, is to assert authority on meta levels of public policy for accumulating more resources to keep a favorable public opinion. Which lands it into a conflict with the deep state and amidst new slogans of accountability. This repeated cycle is going on and on since last 70 years without any critical rapture. Thus those ,the politically and economically excluded, have the right to believe and profess that “the fault is in our stars”.

Asad ur Rehman Born in Punjab, Pakistan is currently residing in Paris as a PHD Candidate. He is interested in transformatory politics in Pakistan