Modern man is caught in a vexing web of a mind-boggling world where a plethora of philosophical premises flying back and forth across the globe, hover heavy over his mind. Amongst scads of philosophies, Nihilism lays and weighs heavy on the postmodern human grey matter. One of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, Nietzsche, the propound of Nihilism, insistingly contends that the life-denying rather life-denigrating morality of Christianity has resulted in modern nihilistic tendencies to combat what he terms the ‘active nihilism’. While on the one hand, the ‘passive nihilism’ as Nietzsche argues, has seared human life in the eddying fires of asceticism, active one can save modern man due to the fact that it enables him to go beyond the irrational, the illogical.

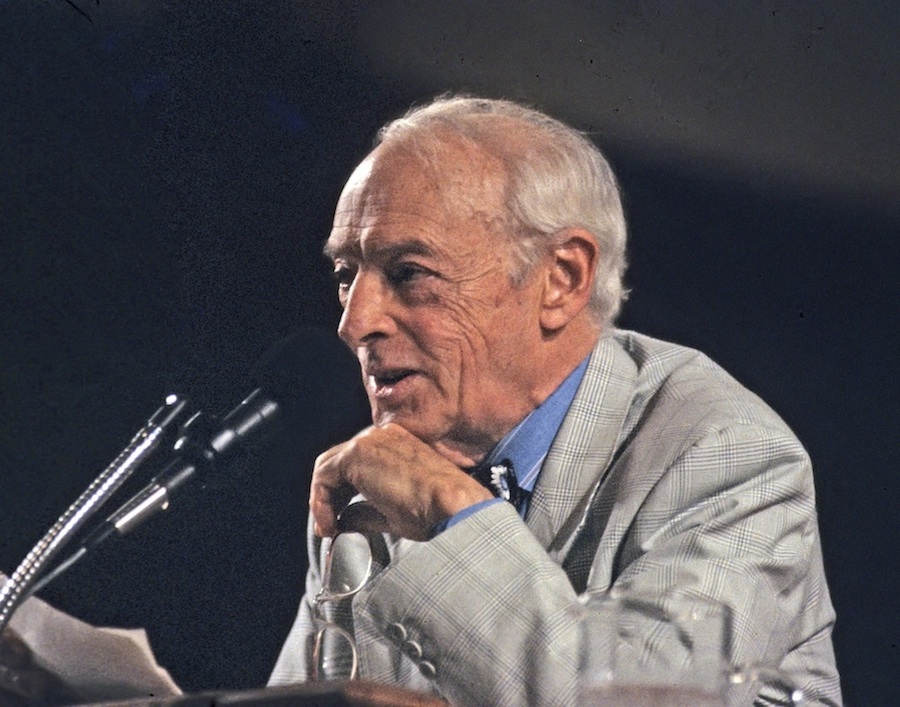

In his novel The Victim (1947) which delineates human anxieties “the angst” in the modern era, a modern thinker and writer Saul Bellow encourages the readers to take the bull of nihilism by its horns and prevail over it. But the path suggested by him differs from the one offered by Nietzsche. He altogether brushes the modern human predicament altogether differently in The Victim by placing its protagonist in a very awful and hopeless ambience, but at the same time displays him pressing all his nerves to carve out a way to supplant and help himself out of the situation. Eventually the realization that to help himself out of the quandary, he must overcome his fear of death only to hug life in totto dawns upon him. Saul Bellow makes his hero acknowledge the bond amongst human race that weaves a sense of responsibility towards one another. It is here that Bellow parts his ways from Nietzsche’s that elevation to higher levels is only gained by the egoistic Ubermensh (roughly translated as Superman).

No doubt, in Bellow’s The Victim, the protagonist suffers from the nihilistic fits of the modern age, but he never falls victim to it and instead attempts to overcome his anxieties and tribulations, finds means and ways to resolve the imbroglio he finds himself in. Tracking back on the origin of modern nihilism to Christian morality, Nietzsche declares that to surmount the ‘passive nihilism’, the life-abnegating asceticism of Christianity should be done away with. He labels the process of such denunciation as ‘active nihilism’ which enables the modern human to transgress beyond the ambit of moral judgments- the source of the ‘passive nihilism’. Since he has antipathy to the other-worldly doctrines and rejects the existence of any creator except human, Nietzsche observes ‘a pattern of eternal recurrences within which life renew[s] itself as energy’, and avers that ‘within this pattern the individual exercise[s] the eternal will survive, to grow and create, to live in the face of suffering, to say yes to life as it renew[s] itself around him.’ This act of saying ‘yes to life’ is what he terms the ‘active nihilism’ and considers the only way to lock horns with the ‘passive nihilism.’

The ‘active nihilism’, however, is not undergone by every Tom, Dick and Harry, but such odyssey can be undertaken only by those who have the aptitude to go beyond the present miserable state of mankind to cruise to the state of Superman or Over-man, claims Nietzsche. Those who are capable of achieving this state, argues he, ‘fulfill’ themselves ‘regardless of the cost to others’, possess ‘the hardier virtues of egotism, cruelty, arrogance, retaliation, and, appropriation’, and despise ‘the softer virtues of sympathy, charity, forgiveness, loyalty, and humanity.’

Bellow picks up the gauntlet against Nietzsche with cogent courage and grounds. Though he confronts nihilism and makes efforts to prevail upon it, the path, the means he chooses doesn’t go Nietzsche’s way. He doesn’t conform to and confirm Nietzsche’s ‘hardier virtues of egotism, cruelty, arrogance’, rather approves of ‘the softer virtues of sympathy…and forgiveness.’ Moreover he seems to disagree with and disregard Nietzsche on the definition of nihilism, as he vociferates:

‘Nietzsche defines nihilism as the dislocation of reigning values…[it] is not an idea, it is an event.’

In The Victim, we find the protagonist doing his best to ‘live in the face of suffering, to say yes to life’, not being ‘regardless’ of what his deeds ‘cost to others’, unlike Nietzsche’s Over-man. Bellow’s novel is concerned with the question of humanity in relation to others and one’s onus of responsibility towards others by vindicating the softer virtues of sympathy and forgiveness. Bellow’s views which run through and through in contradiction to those of Nietzsche are implicitly reflected in a scene of the novel, where he puts his words in the mouth of Schlossberg in a cordial discussion when he is in a café:

‘It is bad to be less than human and it’s bad to be more than human. What’s more than human? Our friend- ‘he meant Leventhal’, was talking about it before. Caesar, if you remember, in the play wanted to be like a god. Can a god have diseases?… We only know what it is to die because some people die and, if we make ourselves different from them, maybe we don’t have to. Less than human is the other side of it…So here is the whole thing, then. Good acting is what is exactly human.’

It is true that Bellow portrays modern nihilism in The Victim but it is again a fact that he offers a way to supplant the nihilistic tendencies by exhorting on the notion of humanity. Unlike Nietzsche who suggests the active nihilism to overcome the passive one, Bellow takes a different route and tries to make man equipped with the intellectual dreams by refuting passivity towards postmodern angst. The lead character in the novel ventures to find a way out of the maze in which he is caught up and thereby gives a new meaning, a new lease to his life. Life-affirming strength highlighted in his ventures is somehow in line with what Nietzsche has underestimated, and what Bellow seeks is ‘exactly human’ not Nietzsche’s Superhuman or superman.

Wani Nazir is a Poet and Educationist based in Indian Administered Kashmir with profound interest in literature.

References:

- Bellow, Saul. (1947), The Victim. New York: Penguin Books

- Lee, Y. (1982). A Seat in Humanity: Saul Bellow’s The Victim. American Studies

- Nietzsche F. (1988). On the Geneology of Morlaity. Trans. M. Clark and A. Swensen. Indianapolis: Hackett