I call it the Abdulla Malik formula for peace of mind and it has the virtue of being applicable to more than one situation, more than one circumstance. One day several years ago, as I walked into Abdulla Malik’s Garden Town house in Lahore, I found him sitting contentedly in a chair on his veranda, with  pile of newspapers and books lying in no particular order on a side table. His mood, always sunny, was even sunnier that day.

pile of newspapers and books lying in no particular order on a side table. His mood, always sunny, was even sunnier that day.

Thinking that maybe word had just been brought to him that the Red Revolution had finally come and right now was drinking tea on McLeod Road, I asked him what the good news was. “I have discovered the ultimate formula for peace of mind,” he replied. “Which is?” I asked.

“I have stopped reading all columnists, each and every one of them, in each and every newspaper that gets delivered to the house every morning. I have never been happier. My mind is uncluttered no longer and I can think clearly.” As for newspapers, he added, “I glance at the headlines and if a particular story interests me, I read through it quickly.”

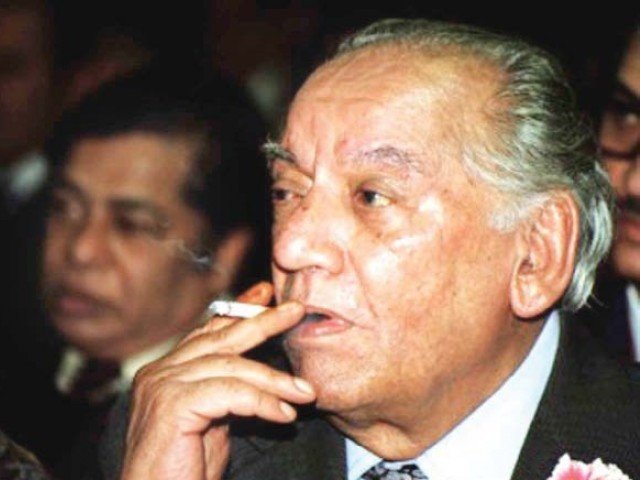

And that reminded us of Faiz Ahmed Faiz. After I complained to him that I was having to read far too many newspapers, Faiz took a long drag at his cigarette and observed, “Bhai akhbar kabhi kabhi dekh laina chahyay. Eham kabar tau patta chal hi jati hai.” (“One may glance at the newspaper once in a while: anything important one comes to know of anyway.”)

And that reminded us of Faiz Ahmed Faiz. After I complained to him that I was having to read far too many newspapers, Faiz took a long drag at his cigarette and observed, “Bhai akhbar kabhi kabhi dekh laina chahyay. Eham kabar tau patta chal hi jati hai.” (“One may glance at the newspaper once in a while: anything important one comes to know of anyway.”)

Out here in Washington, I have implemented the electronic version of the Abdulla Malik formula by getting all Pakistani TV channels unhooked from my satellite dish. Whereas most major Pakistani networks can now be viewed in North America and elsewhere, the programmes they put out bear no relevance to the viewing area or the people of Pakistani origin who live there. There is no effort to relate the programme fare to the communities of Pakistani immigrants who have settled in America, Canada, Britain or Australia. And that is understandable because the entire purpose is to make money and do so at the least cost.

The programmes beamed at us are made up of soap operas, music videos, so-called news bulletins and religious fare. All major Pakistani channels also intone the call to prayer 10 times a day, five for those living in Britain and five for those living in North America. The purpose is not to induce people to remember the Almighty but to save on programme time, which costs money. Ten azans mean roughly an hour for which the channels incur no expense. On one channel the kid sounding the call to prayer is said to be the youngest offspring of the czar who owns it all and then some more.

Those who pray five times a day, are not glued to their TVs. They know exactly the hour when a prayer is due. The hilarious thing is that as soon as the azan is done, the channel returns to whatever rubbish it was showing. Most Pakistanis measure spiritual merit in terms of monetary units, unaware that God’s system of measurement is different.

As for religious programmes, they consist of often abstruse theological discussion. In a country riven by sectarianism, the parading of so-called ulema representing different sects is nothing short of a crime, since the effort should be to unify, not divide. These programmes only widen the fratricidal divide that is destroying Pakistan’s peace and damaging its future.

As for religious programmes, they consist of often abstruse theological discussion. In a country riven by sectarianism, the parading of so-called ulema representing different sects is nothing short of a crime, since the effort should be to unify, not divide. These programmes only widen the fratricidal divide that is destroying Pakistan’s peace and damaging its future.

Then there are the soap operas called dramas, which without exception have just one theme: marriage. It is either a marriage that is to take place and has not; or a marriage that has taken place but is not doing well because of the mother-in-law, a former lover, a money problem, a jealous sister-in-law or a husband who has taken to drink or gambling.

But worry not, without fail the drama ends either with wedding bells or on a note of happy reconciliation. In a country and a culture that has more social, political, spiritual, legal and psychological problems than anyone has the ability to count or list, it is reprehensible to reduce them to the single theme of marriage. In any case, marriage needs the least promotion in a grossly overpopulated country like Pakistan.

But what finally got my goat in terms of Pakistani TV channels was the Mumbai carnage. While the siege of that great city continued as ten terrorists went on their killing spree, mowing down men, women and children without pity or remorse, our television networks continued with their cooking shows, music videos, inane soap operas and religious lectures and azans.

For close to three days, CNN suspended all programming to devote itself exclusively to non-stop coverage of what was happening in Mumbai. The indifference with which our channels treated this huge and tragic event was hard to understand and even harder to accept. To this day, when piles of evidence have been produced to prove that all 10 attackers were Pakistanis, everyone in Pakistan, especially on TV, is in denial.

And what of the news that is put out? It is actually radio news packaged as television news. One is told what is being said by A, B or C. You see their mugs, their lips moving but you rarely hear them speak their own words. There is hardly ever any live footage and people’s own voices. It is mostly stock and the viewer is not even told that what he is watching on the screen is not actuality. This is dishonest and it is pathetic.

Television came to Pakistan, thanks to Altaf Gauhar, in 1964, which was 44 years ago; and to think that this is all the progress we have made. What our channels show as news is an insult to the viewer. Then there is the ticker, or the “feeta”, which should only bring important developments to the viewer’s notice but that is one thing it rarely does.

Then there are the talk shows with their self-proclaimed experts, few of whom can stake a claim to the title. And yet they go on yapping, rarely listening to one another but declaiming their views because they obviously love the sound of their own voice. Sometimes if there are four or five of them in a show, and they all talk at the same time, producing gibberish.

In short, you don’t have to watch Pakistani TV to know what is going on. In fact, if you want to know what is not going on, that is the switch you should flick.