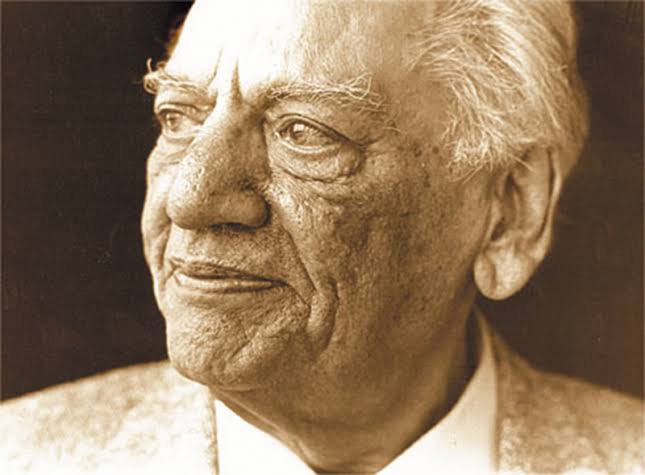

On a one-to-one basis, my personal contact with Faiz has been fewer than a dozen times. All these get-together meetings for a personal powwow took place in London during the seventies of the last century. One last meeting with him was in 1983, a year before his demise at the relatively young age of 73. Let me explain. I have never publicized my friendly contact with him and, therefore, much has remained hidden. I shunned Mushairas and Mehfils organized by the local Urdu elite and kept my distance. It was either he or Chacha Mulk who gave me a phone call at my residence in Milton Keynes where I was a research associate at the British Open University. Chacha Mulk (the renowned novelist Mulk Raj Anand) didn’t drive himself and he would ask me to bring my small Morris Minor, pick him up from Indian High Commission’s Guest House and take him to Faiz.

Faiz was twenty years my senior; Chacha Mulk was twenty-seven years older than me. Another example is Saqi Farooqi who was a quarter-century junior to Faiz as also to Noon Meem Rashid and yet had a warm and intimate friendship with both. Let me add in haste that friendship is neither bound by age nor by gender. It only partakes of common interests, concerns, conversation topics – and most important of all, participating partners’ level of intellect, education, mental caliber, and parlance of conversation. I believe that he was more akin to me in this respect than to Mulk. Maybe one reason was that Mulk just garbled his Urdu and was never adept in speaking that language.

The one and only exception to my rule of no public display of our sporadic contact and my reverence for him or his affection for me was the irreverent poem I wrote about him the same day that I met him in 1983. I published the poem six years after his death. Titled Aik Nadaar Mulk ka Shair,ایک نادار ملک کا شاعر(Poet of a Poor country), this poem is included in my poetry collection DAST E BURG (1990). It was written in a somber mood. When I met Faiz that evening, I found not his usual assured self, but a fearful, broken man lurking in him. I forthwith knew that he was shattered both in his life-long belief in Communism as also in his health. His conversation with me bore testimony to this loss of faith.

He was suffering from Fistula and was in pain. He had come back from a visit to the Soviet Union which was at the brink of dissolution and the chaos before its final break into bits and pieces across Europe and Central Asia. This time he was staying not at Zohra Nigah’s زہرہ نگاہ house, but at a different location. If my memory serves me right, it was an apology of a house (so small it was!) in Bamsbury, across Kings Cross Road where it changes its name to Euston Road. Just whose property it was I never inquired. His wife and Muneyza, منیزہ his daughter, both were with him. Salma سلمہwasisn’t there. As we know, his two daughters were married to two Hashmi ہاشمی brothers, Shoaib شعیب and Humair. حمیر

Leaving my personal reminiscences of Faiz’s personality to the later installments of this article, I will now take up the most important aspect – his poetry, as I evaluate it now.

The first quality of Faiz’s poetry that strikes me is its visual imagery that permeates into the essential musicality of his verse. After Iqbal, Faiz has this quality in abundance; the difference is بلند آہنگی loud tenor) in Iqbal and the silk-like soft and sometimes cloyingly sweet tenor of Faiz. This quality is less apparent in other Taraqqi Pasand poets. Faiz cultivated the ghazal format in a neo-classical or post-romantic genre – and he brought a marriage of convenience between the classical and romantic modes. It is in this context that the second generation of Progressive poets took their content, communicability, style, and even the Faiz-inspired parlance of ghazal to its zenith. It became almost a fad with poets. “Thus Faiz’s poetic felicity, choice of words, coinages, allusions, neo-classical reliance on the true-classical patterns of ghazal became the order of the day.”

The quality that differentiates Faiz from, say Josh Malihabadi, both in his nazms and ghazals, is that that he leaves things unsaid or half-said or just hinted at or given a symbolic or metaphoric treatment to achieve a shareable quality of modes of poetic experience with the reader. Josh, on the other hand, doesn’t leave anything unsaid. I would use the words “poetry as a slogan” and “poetry as a sweet whisper” in the case of these two poets.

(Two other parts to follow)